Resources

Search our content by topic, type, industry, or whatever keyword you like.

Filter by Industries, Categories or Both.

Case studies

|

Sewer

Sewer

208032673932

Surveying 450 meters of damaged sewers in 1 day at Niagara...

Blog

|

Infrastructure

Infrastructure

207445138869

How the Maryland Department of Transportation State Highway...

News

|

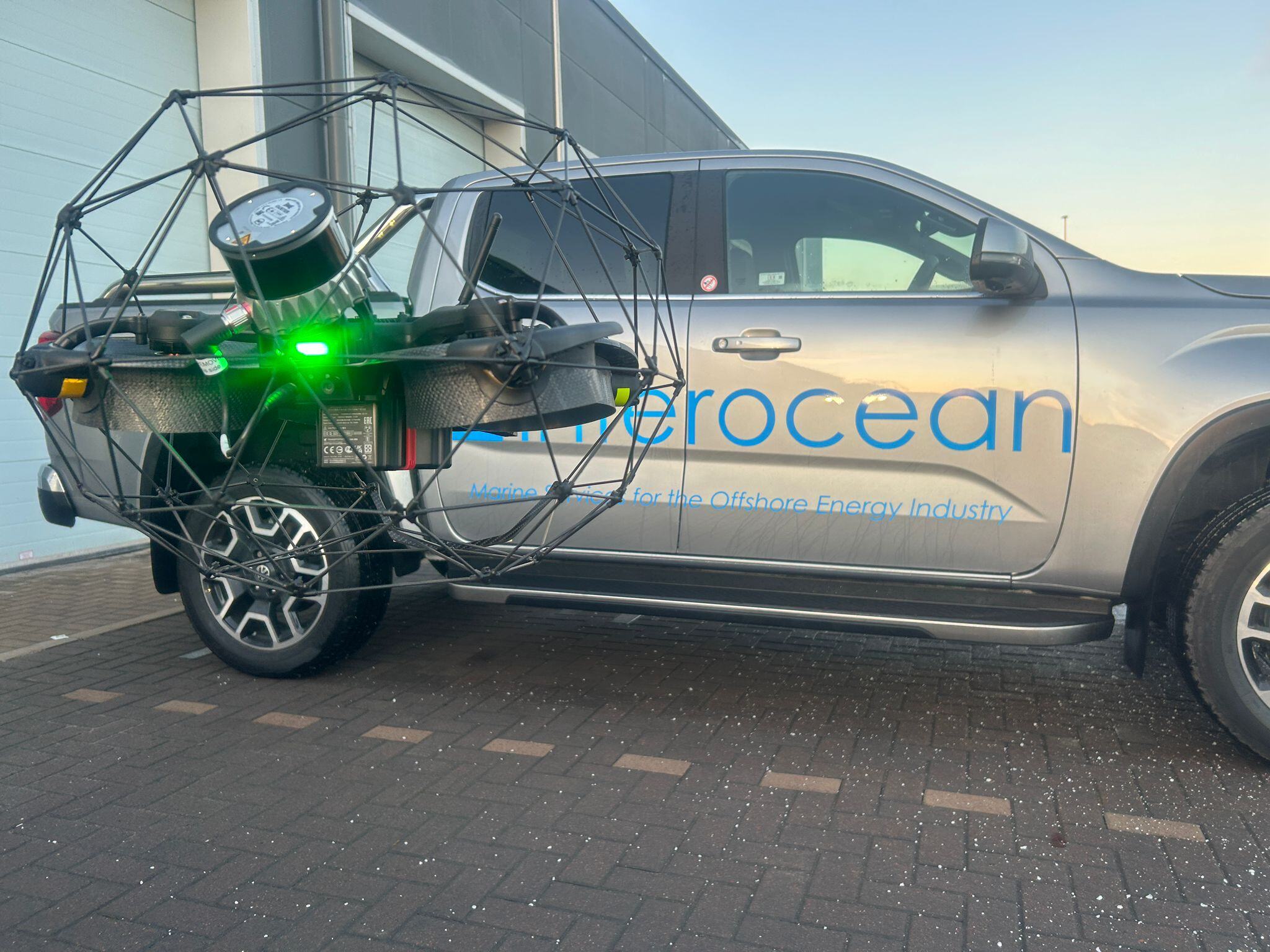

Maritime

Maritime

206200291122

Flyability To Host Maritime Drone Days in Athens with...

Case studies

|

Mining

Mining

203585154711

125% more data in gold mine stope surveys with the Elios 3

-Jan-16-2026-10-59-56-8006-AM.png)

Case studies

|

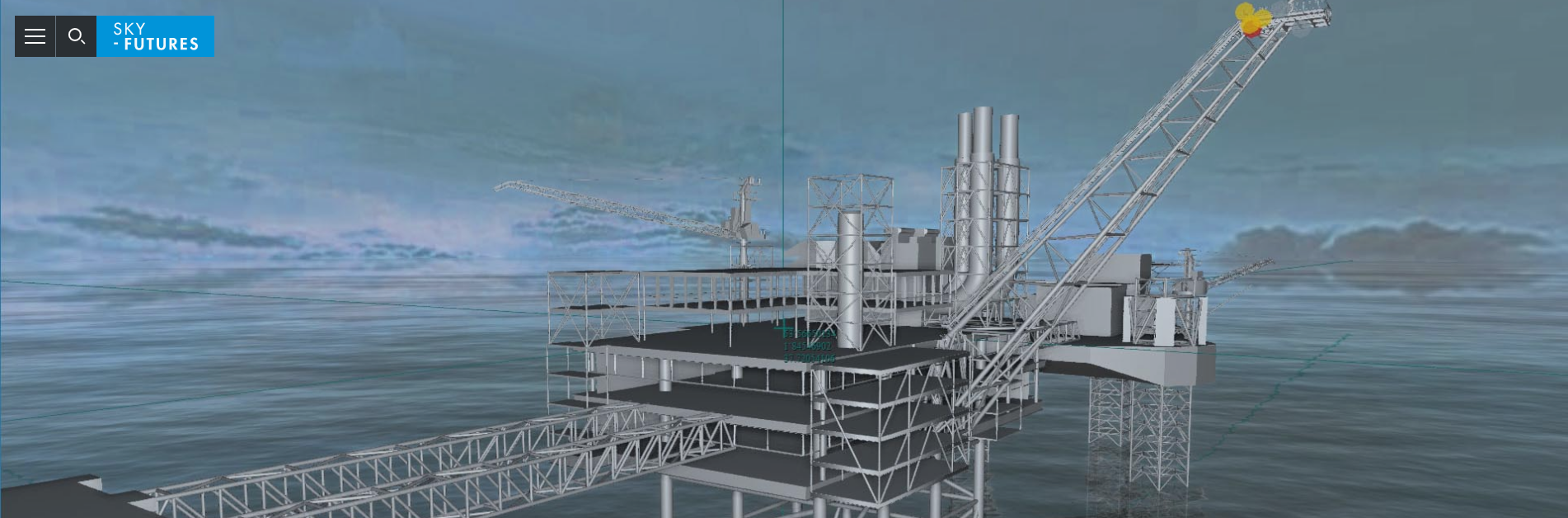

Maritime

|

Oil & Gas

Maritime Oil & Gas

199902388079

CAN-USA and Shell Redefine Offshore Inspections with the...

.jpg)

Factsheets

|

Maritime

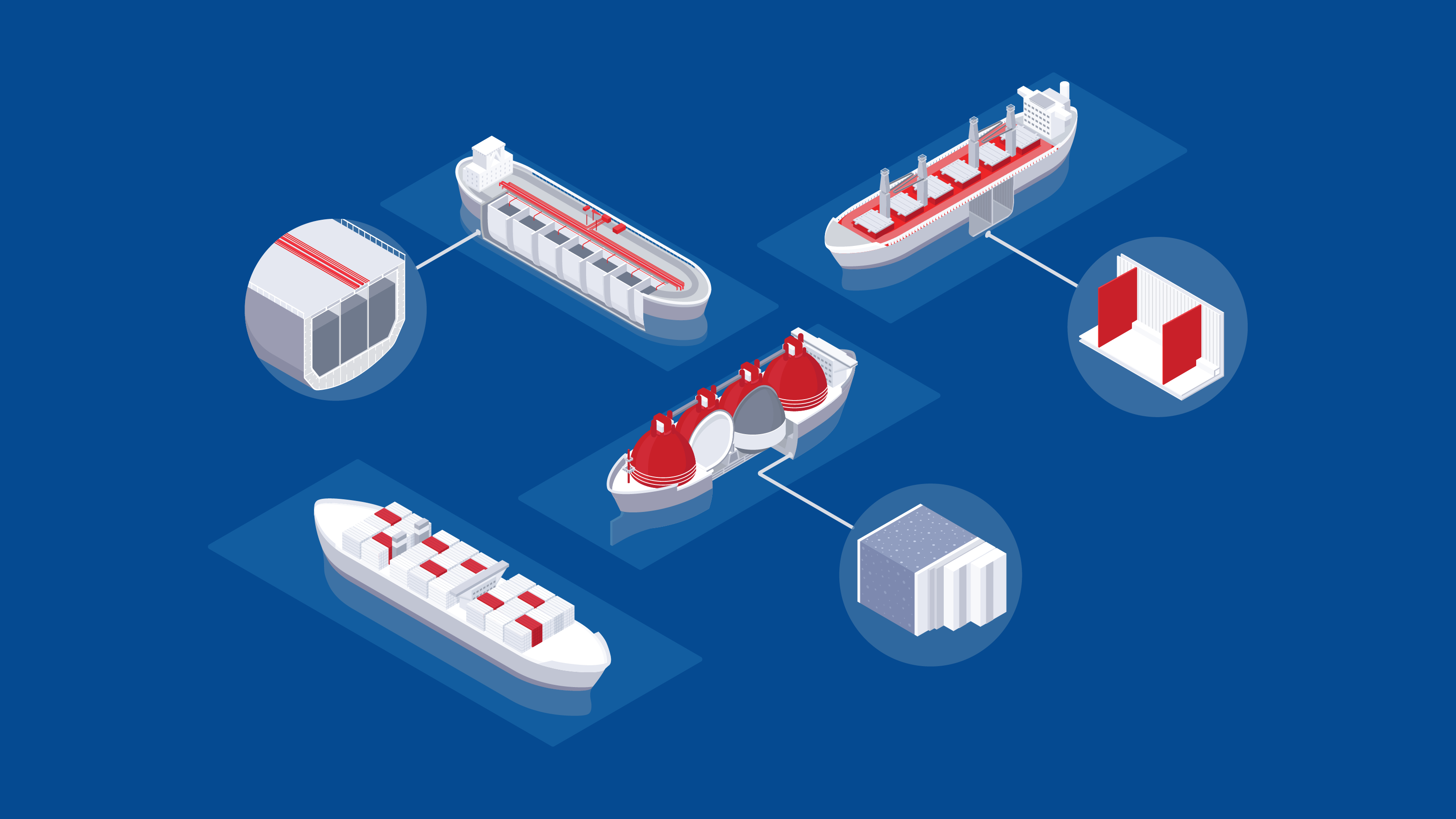

Maritime

204229780871

Discover Maritime Drones for Remote UT and Visual...

Factsheets

|

Oil & Gas

Oil & Gas

205365949272

Discover Oil and Gas Drones for remote NDT inspections

.jpg)

Case studies

|

Infrastructure

Infrastructure

203272401011

Inspecting Indoor Waterparks with the Elios 3

.png)

Case studies

|

Sewer

Sewer

202599713641

From Days of Work to a 30-Minute Flight for Oil Water...

Case studies

|

Power Generation

Power Generation

201807163781

Drone inspection cuts 300 hours of work in emergency...

-1.png)

Blog

|

Maritime

Maritime

201735712790

Get Certified with ABS to use the Elios 3 UT Drone for...

Webinar

200078497304

Flyability Cloud: Colorization, Feature Updates, and Live...

News

|

Infrastructure

Infrastructure

200936278284

Jaguar Land Rover Boosts Factory Safety and Efficiency by...

Case studies

|

Infrastructure

Infrastructure

199476167513

Inspecting Elevator Shafts with the Elios 3 in New york

News

|

Oil & Gas

Oil & Gas

198920126373

Saudi Aramco award the use of caged drones for internal...

News

|

Maritime

|

Oil & Gas

Maritime Oil & Gas

196863570522

From Ropes to Drones - A look into Shell and CAN-USA's use...

Case studies

|

Mining

Mining

197588999746

From 8 Hours to 20 Minutes for an Ore Pass Inspection with...

News

|

Maritime

|

Oil & Gas

|

Mining

Maritime Oil & Gas Mining

195106999201

Flyability Launches Tether Power Unit for the Elios 3 for...

Factsheets

|

Sewer

Sewer

194809428911

How Are Drones Reinventing Sewer Management Worldwide?

News

|

Infrastructure

Infrastructure

195050335881

The Elios 3 Wins Major Hong Kong Construction Safety Award

Factsheets

|

Power Generation

Power Generation

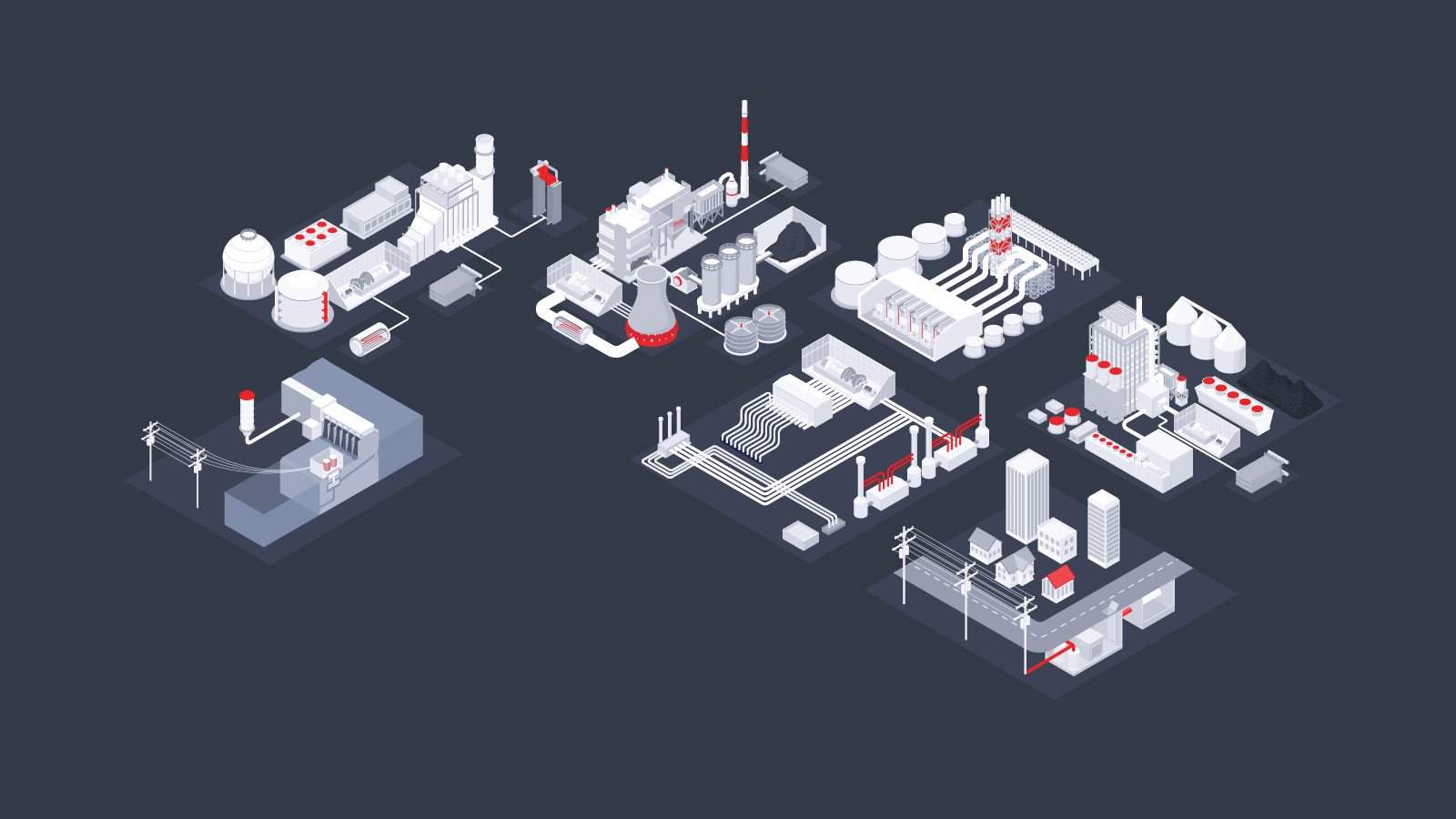

186969916440

Why are Power Plants Investing in Inspection Drones [Free...

Blog

|

Chemicals

|

Infrastructure

Chemicals Infrastructure

194410465623

Making inspections 50% faster for Nippon Steel Technology...

Webinar

|

Mining

{name=Mining, label=Mining}

192646748966

Uncovering the Role of Surveying Drones in Mining

Case studies

|

Food & Beverage

Food & Beverage

193189468336

ROI of Drone Inspections: How Cargill Successfully Deploys...

Case studies

|

Mining

Mining

192769032195

Saving $500,000 for Post-Blast Inspections at an...

Case studies

|

Power Generation

Power Generation

192747228479

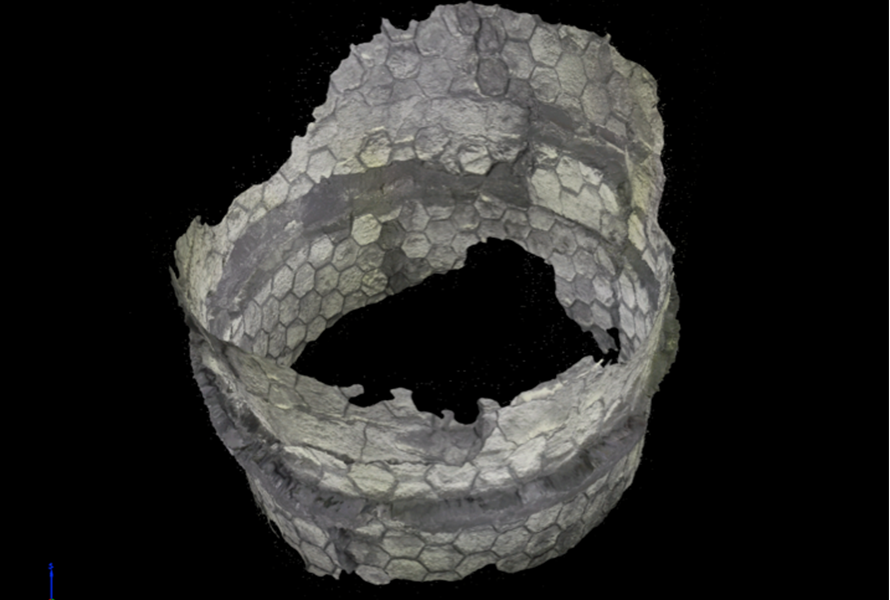

7-Minute Drone Penstock Inspections with the Elios 3

News

|

Maritime

Maritime

192510000948

Flyability wins the Safety and the Innovation Award from...

News

|

Mining

Mining

191707878750

Flyability announces new high-capacity batteries amid...

Blog

|

Power Generation

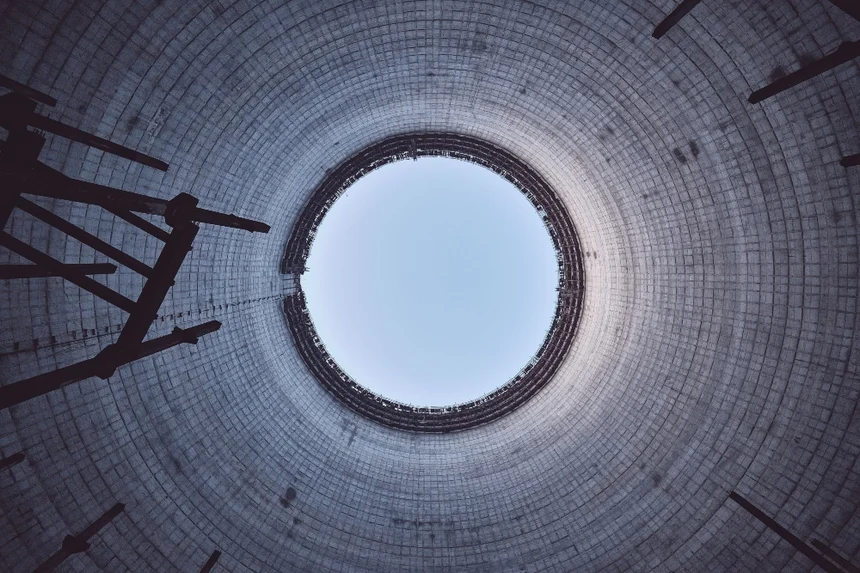

Power Generation

191709422714

How Drones are Improving Cooling Tower Inspections

White papers

|

Mining

Mining

190956009311

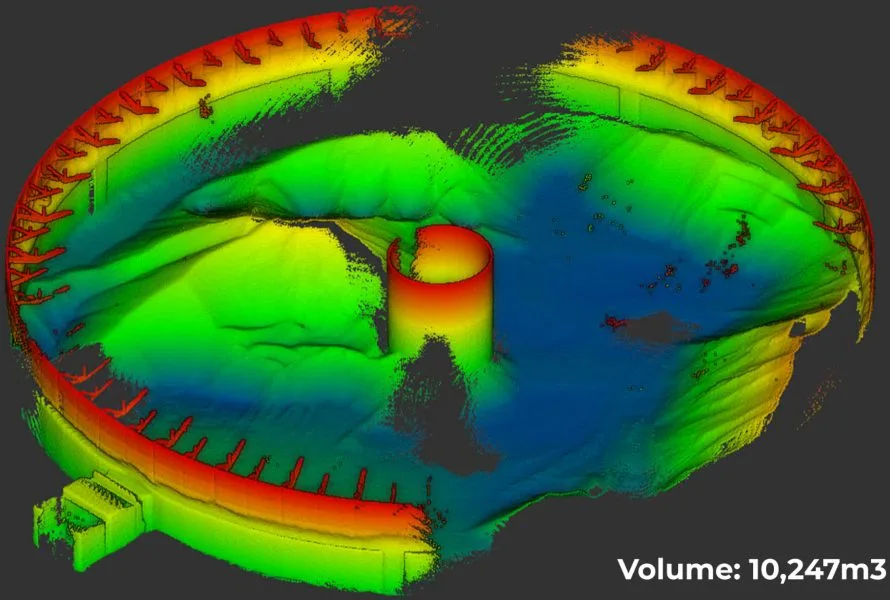

Guide: Volume Measurements with Leica Cyclone 3DR

Factsheets

|

Power Generation

Power Generation

186858295829

Penstock inspections with the Elios 3 UT drone

Case studies

|

Sewer

Sewer

190355450670

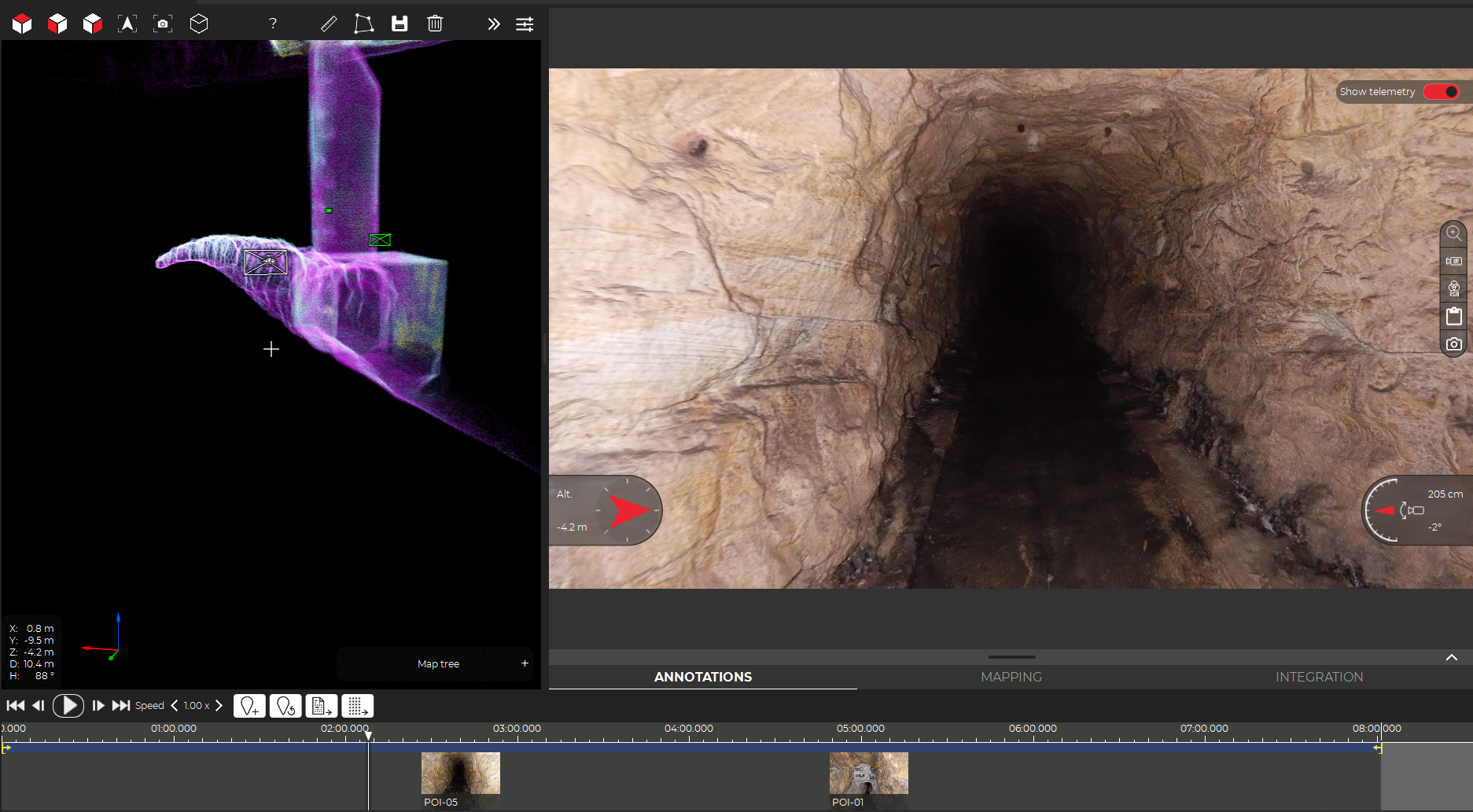

Inspecting 260 meters of stormwater drains with the Elios 3...

Case studies

|

Infrastructure

Infrastructure

190181392672

Safety First: Flying the Elios 3 Drone Inside a Burnt...

Factsheets

|

Power Generation

Power Generation

186856049847

Boiler Inspections with the Elios 3 drone

Factsheets

|

Power Generation

|

Nuclear

Power Generation Nuclear

187153919644

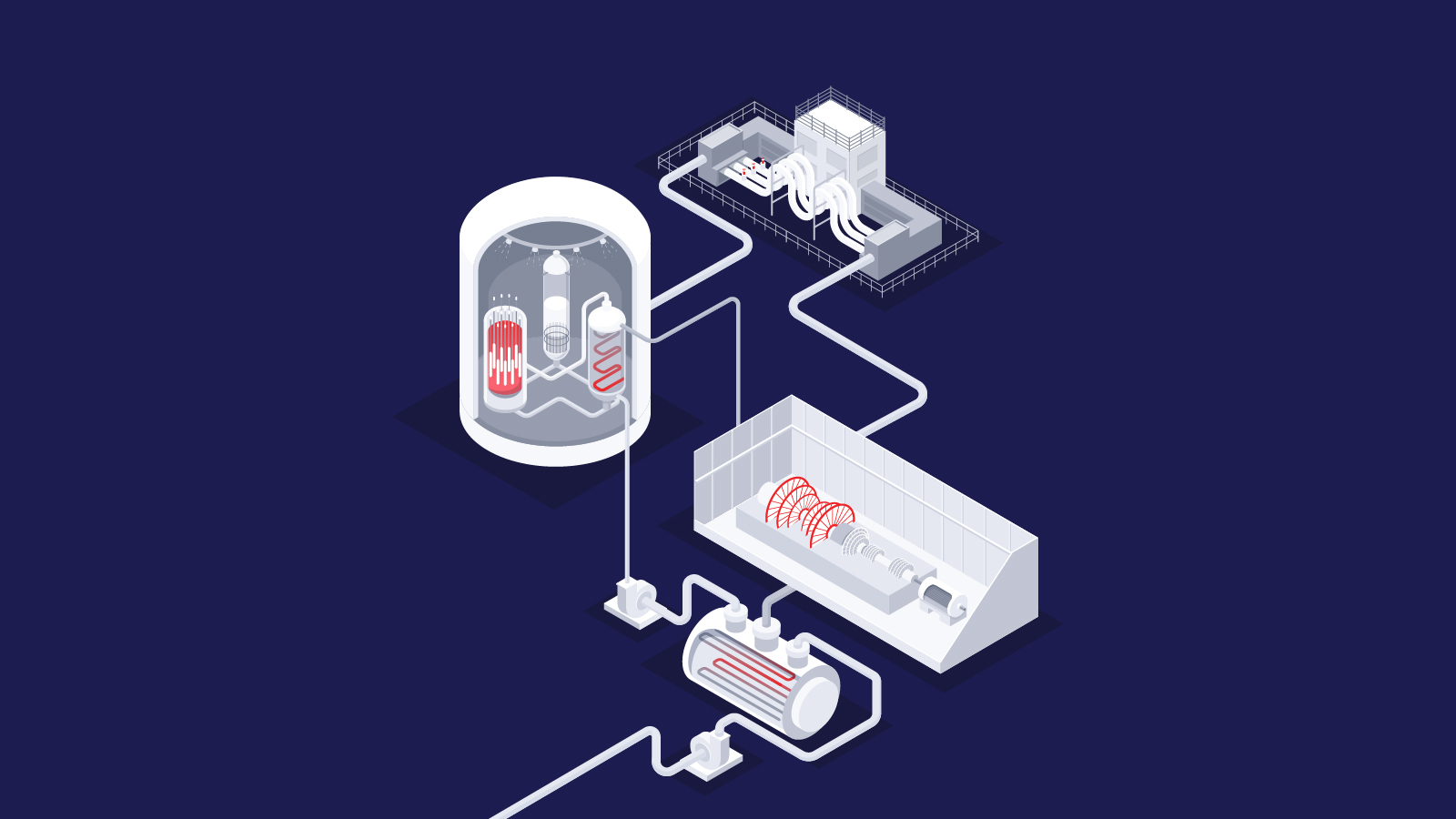

Condenser inspections with the Elios 3 UT drone

Case studies

|

Power Generation

Power Generation

189292963632

Saving 450,000 Euros on Boiler Inspections with the Elios 3...

Case studies

|

Power Generation

Power Generation

188852414099

Saving 20% on Stack Inspections with the Elios 3

Blog

|

Power Generation

Power Generation

188723047959

Lighting Up: The Benefits of Drones in Power Generation

News

|

Maritime

Maritime

188478880636

Flyability Awarded Innovation Endorsement Certification by...

Factsheets

|

Power Generation

Power Generation

187969593231

Wind turbine blade inspections with the Elios 3 drone

Webinar

|

Power Generation

{name=Power Generation, label=Power Generation}

187222447652

Wind Turbines and the Elios 3: Seeing More

Blog

|

Power Generation

|

Nuclear

Power Generation Nuclear

186336255113

10 Elios 3s and Counting: How Dominion Energy Set Up a...

White papers

|

Mining

|

Infrastructure

Mining Infrastructure

187493394294

Whitepaper: Accuracy Report on the Elios 3's LiDAR Payloads

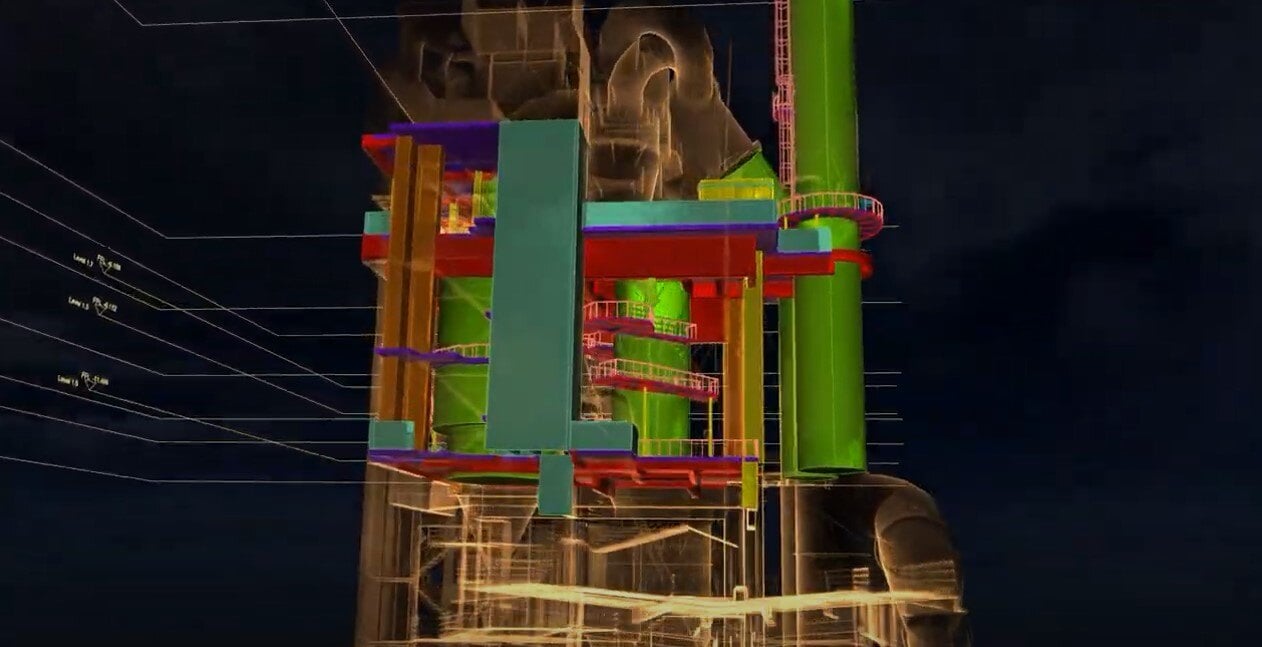

White papers

|

Cement

|

Infrastructure

Cement Infrastructure

187491266838

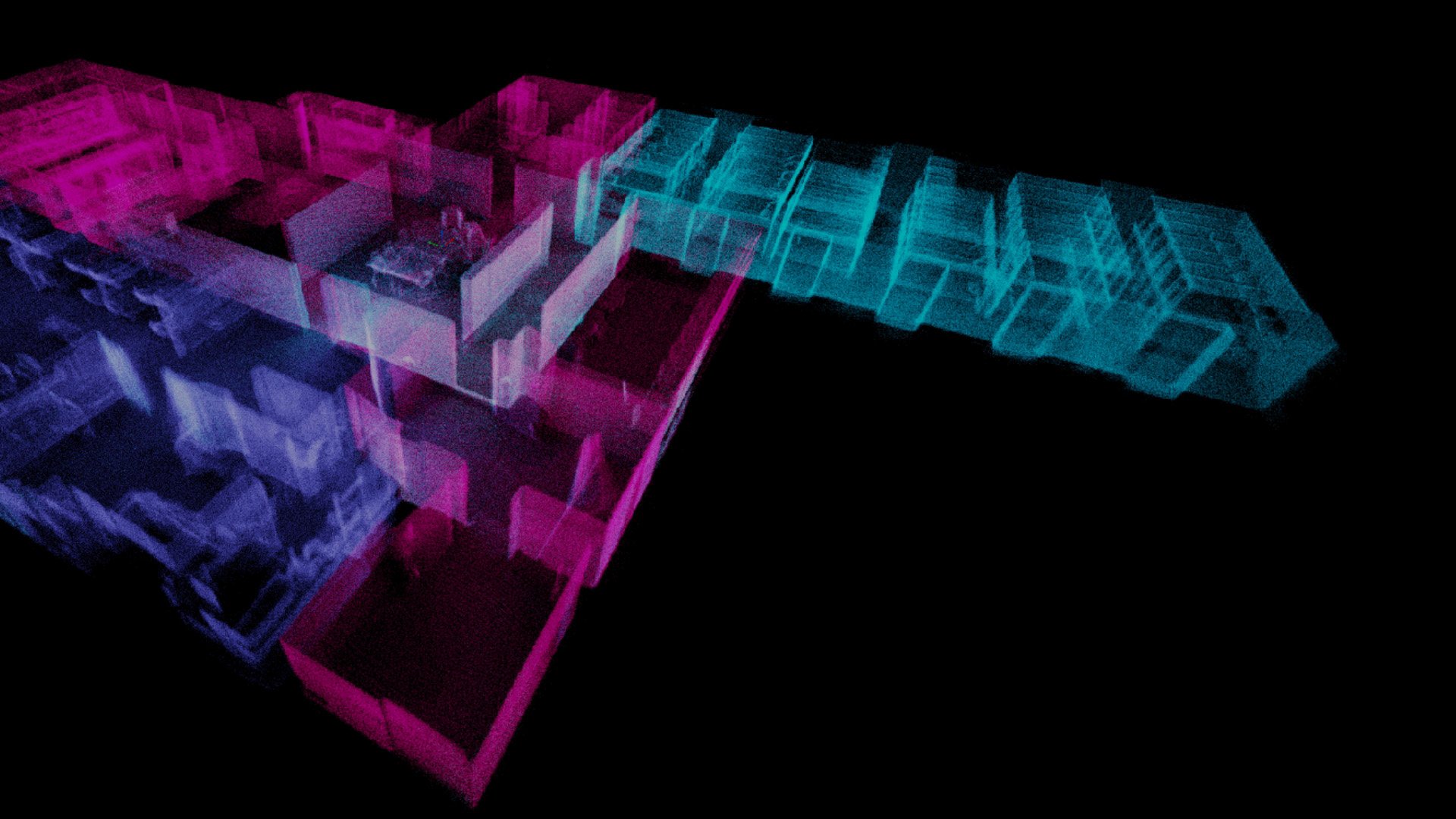

Guide: Manual for Scan to BIM with the Elios 3

White papers

|

Cement

|

Infrastructure

Cement Infrastructure

187486153893

Whitepaper: Assessing the Elios 3’s for Scan to BIM

Case studies

|

Mining

Mining

187449484869

Drones for Mining in South Africa: An Interview with...

Blog

|

Power Generation

|

Oil & Gas

|

Mining

Power Generation Oil & Gas Mining

187446134570

Videos: 6 Ways to Use the Elios 3 Drone for 3D Models

White papers

|

Mining

|

Cement

Mining Cement

187320446109

Guide: Measuring Volumes in Complex Environments

White papers

|

Mining

|

Cement

Mining Cement

187217986636

Whitepaper: The Elios 3 Compared to Terrestrial Laser...

Case studies

|

Power Generation

Power Generation

187271248737

How VZU Plzen Achieved an 80% Reduction in Penstock...

-3.jpg)

Webinar

|

Power Generation

{name=Power Generation, label=Power Generation}

186327732064

Drones in Power Generation: The Elios 3 Inspecting Boilers,...

Case studies

|

Maritime

|

Oil & Gas

Maritime Oil & Gas

186347658382

Saving $600,000 On COT Inspections With The Elios 3 UT

Case studies

|

Power Generation

|

Nuclear

Power Generation Nuclear

186296854181

Cutting Condenser Inspections From 8 Days To 8 Hours

News

|

Maritime

Maritime

185838361381

Flyability's Elios 3 UT Wins Safety Award at Offshore...

News

|

Sewer

Sewer

185141898377

Flyability and WinCan Announce Custom Integration for Elios...

.png)

Webinar

|

Power Generation

{name=Power Generation, label=Power Generation}

184616941159

Powered Up: The Elios 3 in Nuclear Energy

Blog

|

Chemicals

|

Oil & Gas

|

Mining

Chemicals Oil & Gas Mining

185059614726

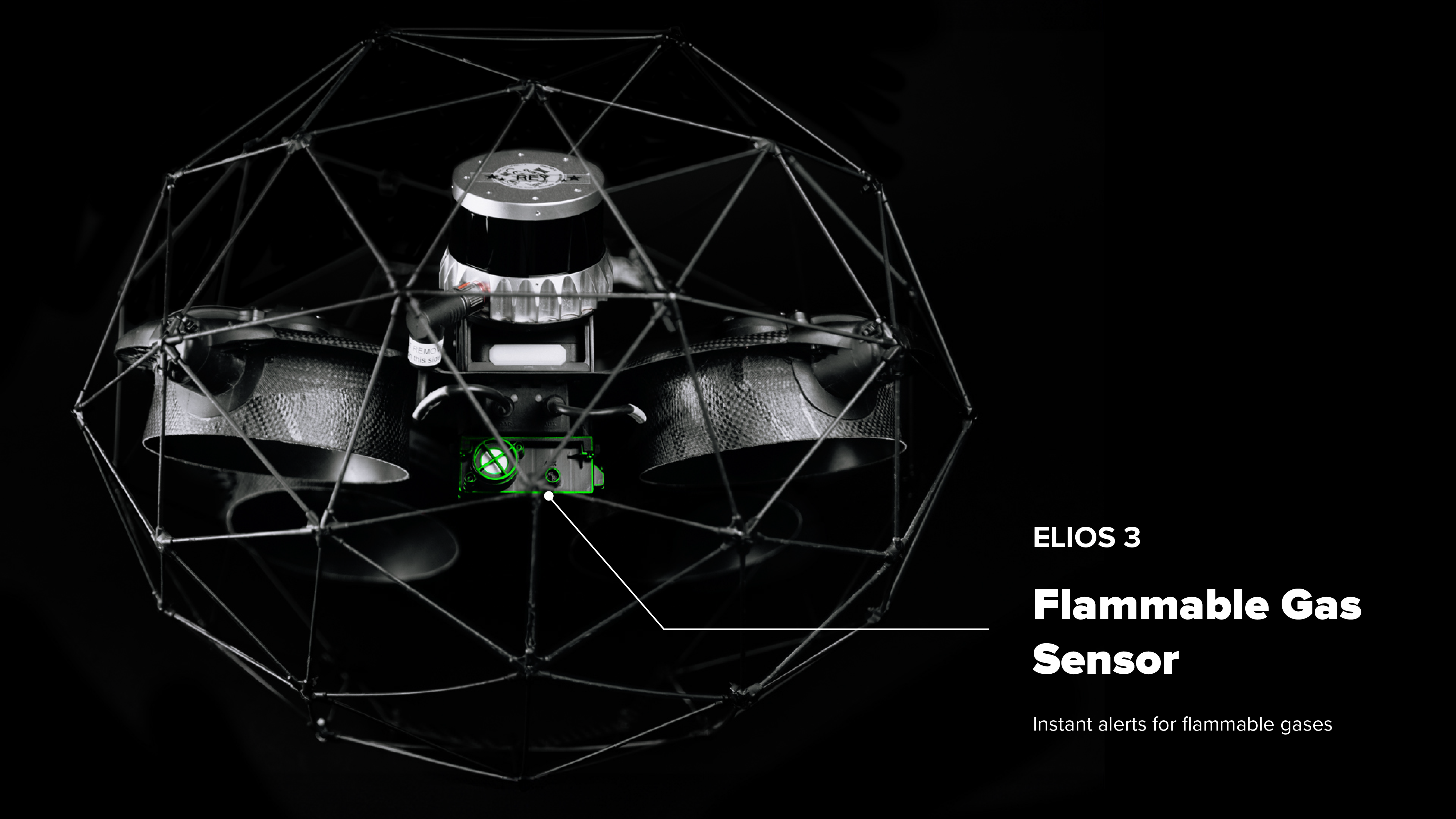

What Does Intrinsically Safe Mean?

Blog

|

Chemicals

|

Oil & Gas

|

Mining

Chemicals Oil & Gas Mining

185021452565

What Does ATEX Mean?

Blog

|

Nuclear

Nuclear

184753357166

How Indoor Drones at Nuclear Sites Reduce Radiation Exposure

Case studies

|

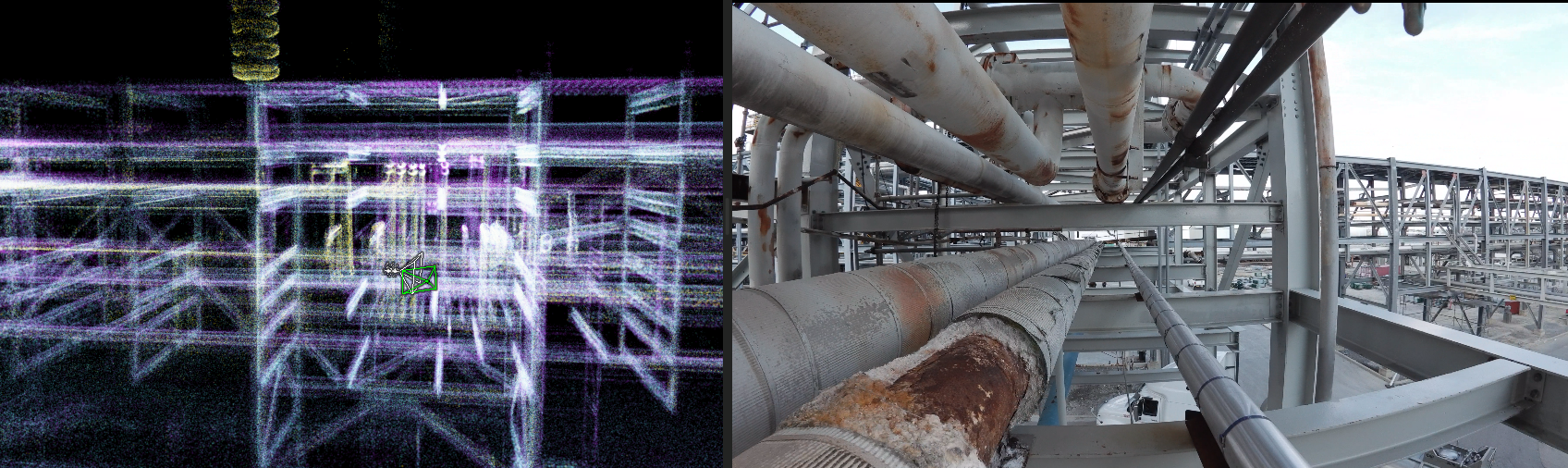

Oil & Gas

Oil & Gas

184567772756

Cutting Costs by 60% for Pipe Rack Inspections with the...

Blog

|

Chemicals

Chemicals

183852952963

7 Key Benefits of Drone Inspections in the Chemical Industry

Blog

|

Maritime

Maritime

183719002486

Interview: Class Certification for Maritime Drone...

Blog

|

Oil & Gas

Oil & Gas

181881010280

7 Key Benefits of Drone Inspections in Oil and Gas

Case studies

|

Nuclear

Nuclear

180501521031

How Much Radiation Can the Elios 3 Handle? Testing at a DoE...

News

|

Cement

Cement

177403710036

Building Expertise: Flyability and Holcim's North America...

Webinar

|

Infrastructure

{name=Infrastructure, label=Infrastructure}

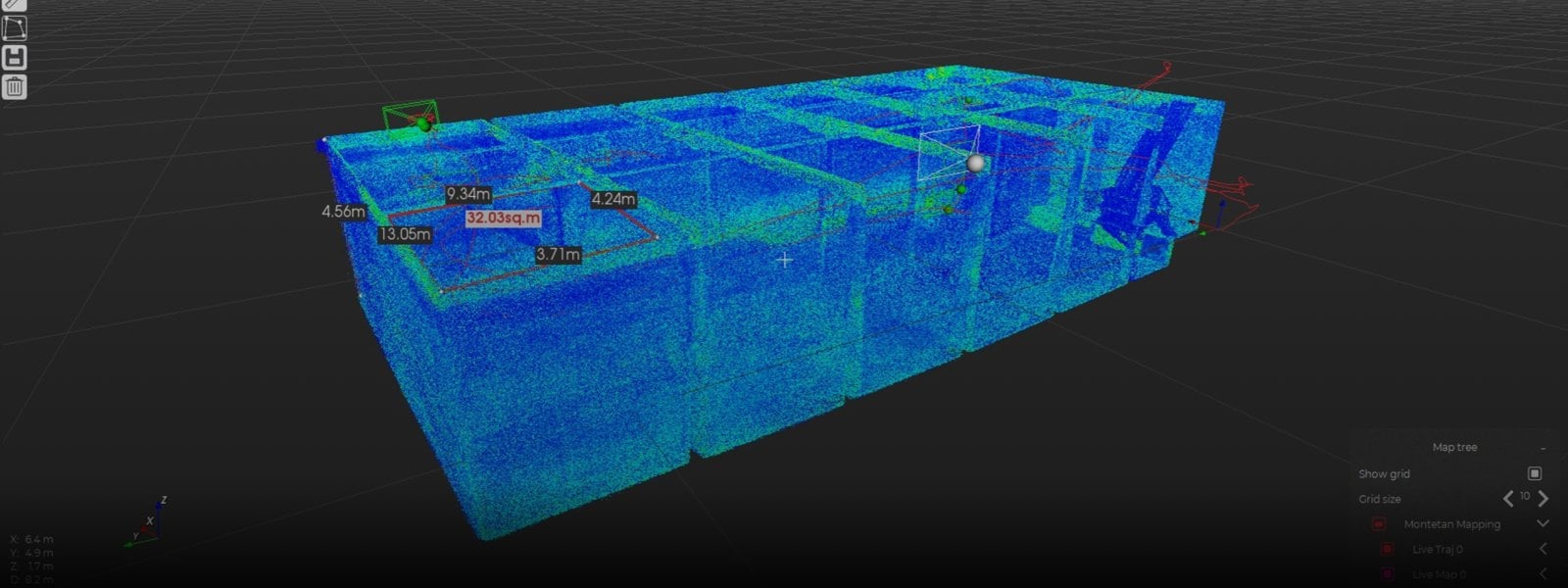

174912905880

Unlocking Scan to BIM with the Elios 3

Case studies

|

Power Generation

|

Oil & Gas

Power Generation Oil & Gas

176364570281

Tank Ultrasonic Thickness Measurement With The Elios 3

Case studies

|

Mining

Mining

175751758009

A Storage Bin Inspection with the Elios 3 at a mine

Case studies

|

Power Generation

Power Generation

173959040527

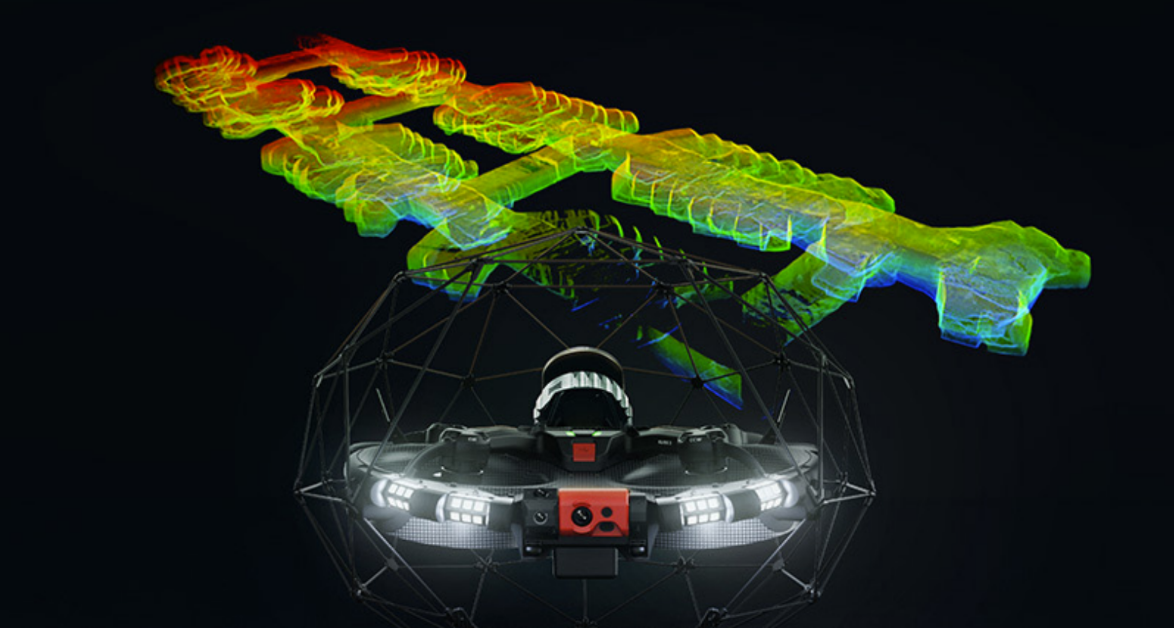

Drone wind turbine blade inspections with the Elios 3

Case studies

|

Infrastructure

Infrastructure

173843256620

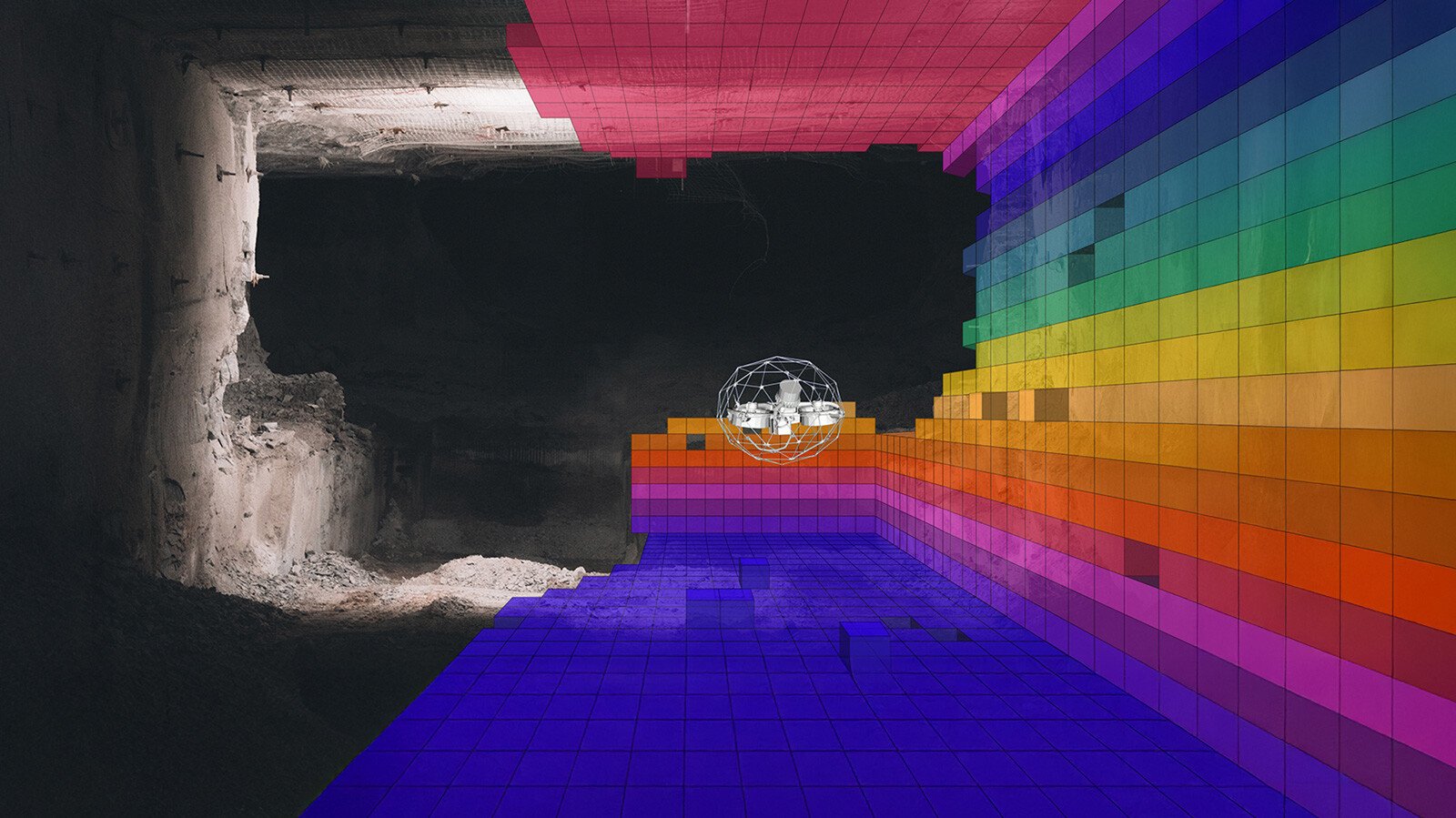

Investigating a collapsed tunnel after a landslide in the...

Case studies

|

Infrastructure

Infrastructure

173334266236

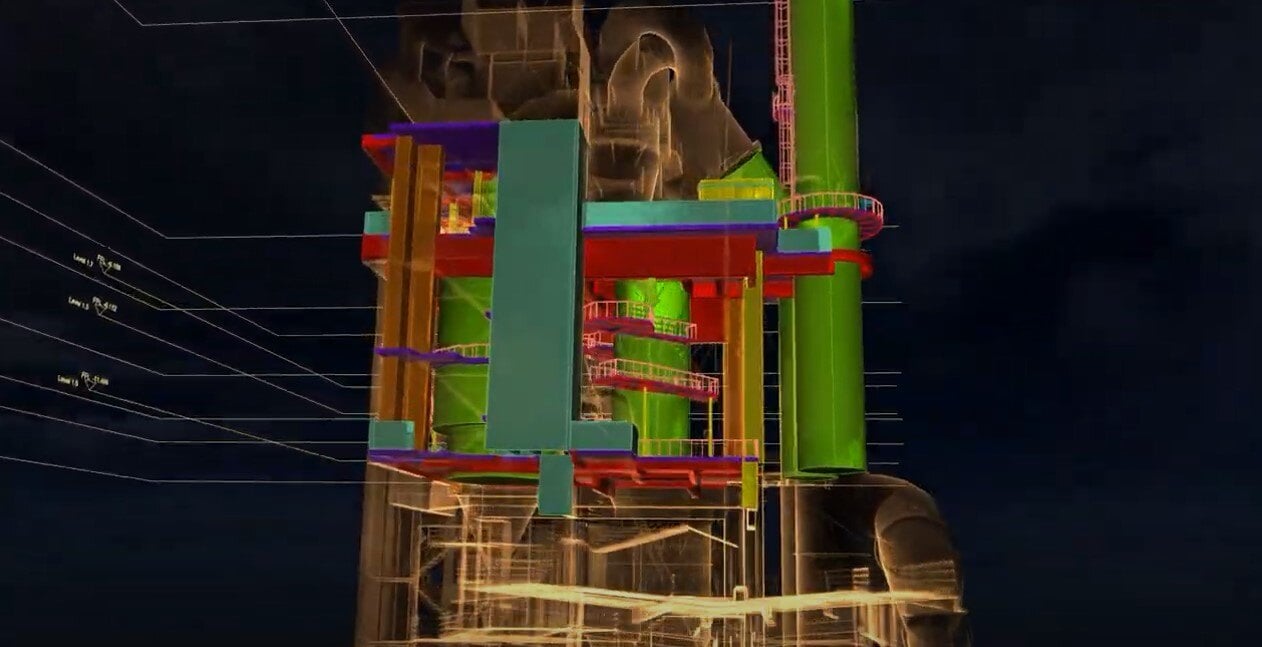

Drone Scan to BIM: the Elios 3 digitizes a cement plant

Blog

|

Mining

Mining

172508753466

Drones for Mining: Safety, Efficiency, and Data Collection...

Webinar

|

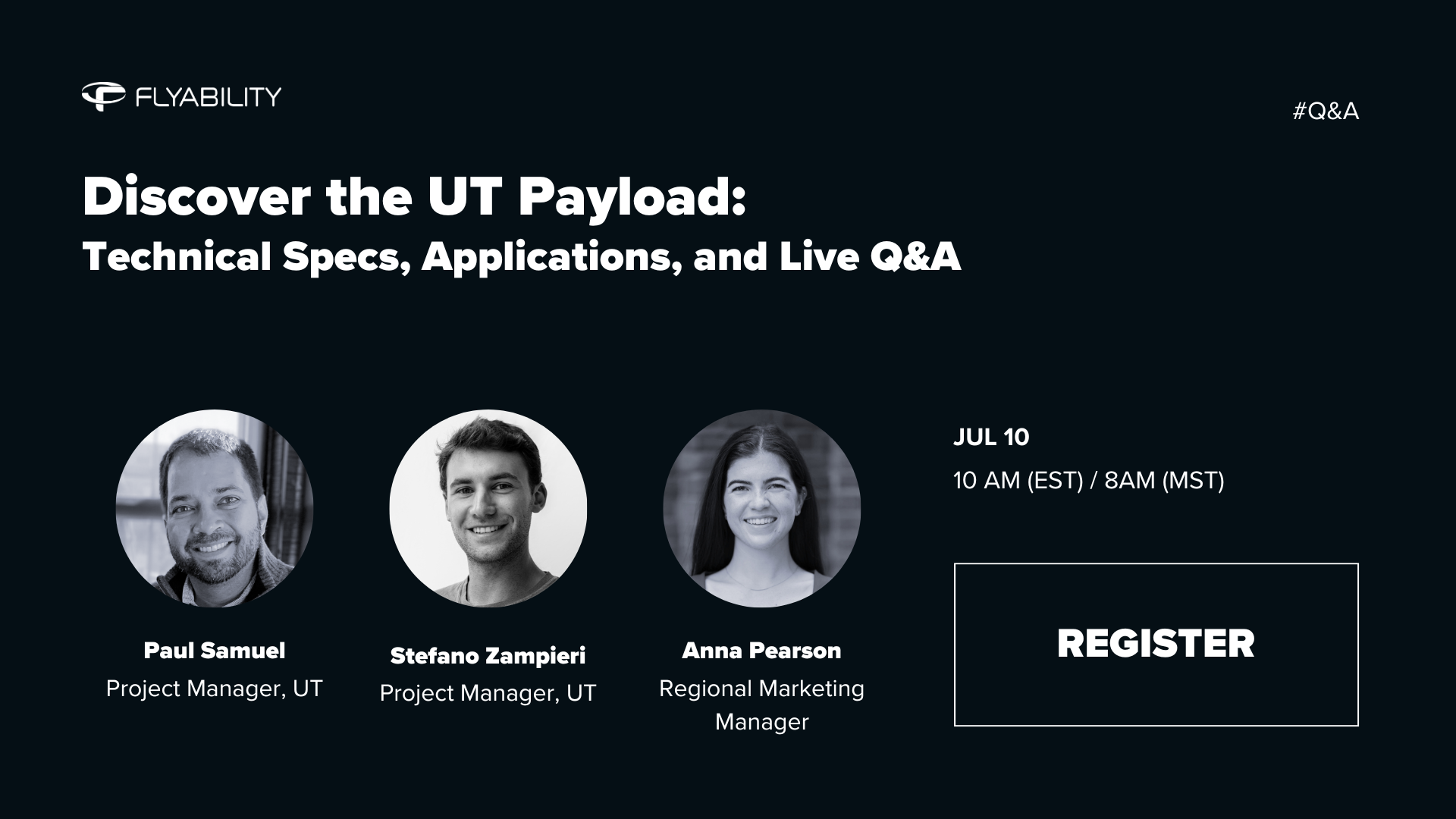

Oil & Gas

{name=Oil & Gas, label=Oil & Gas}

171466793731

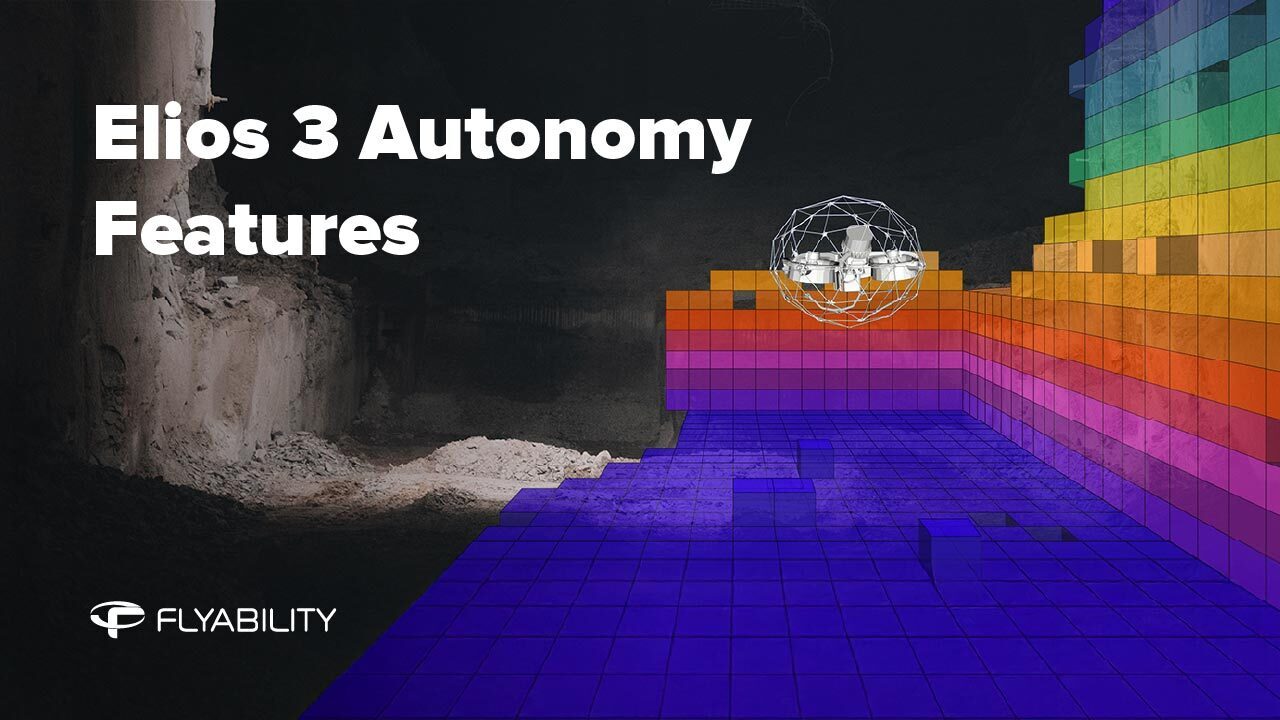

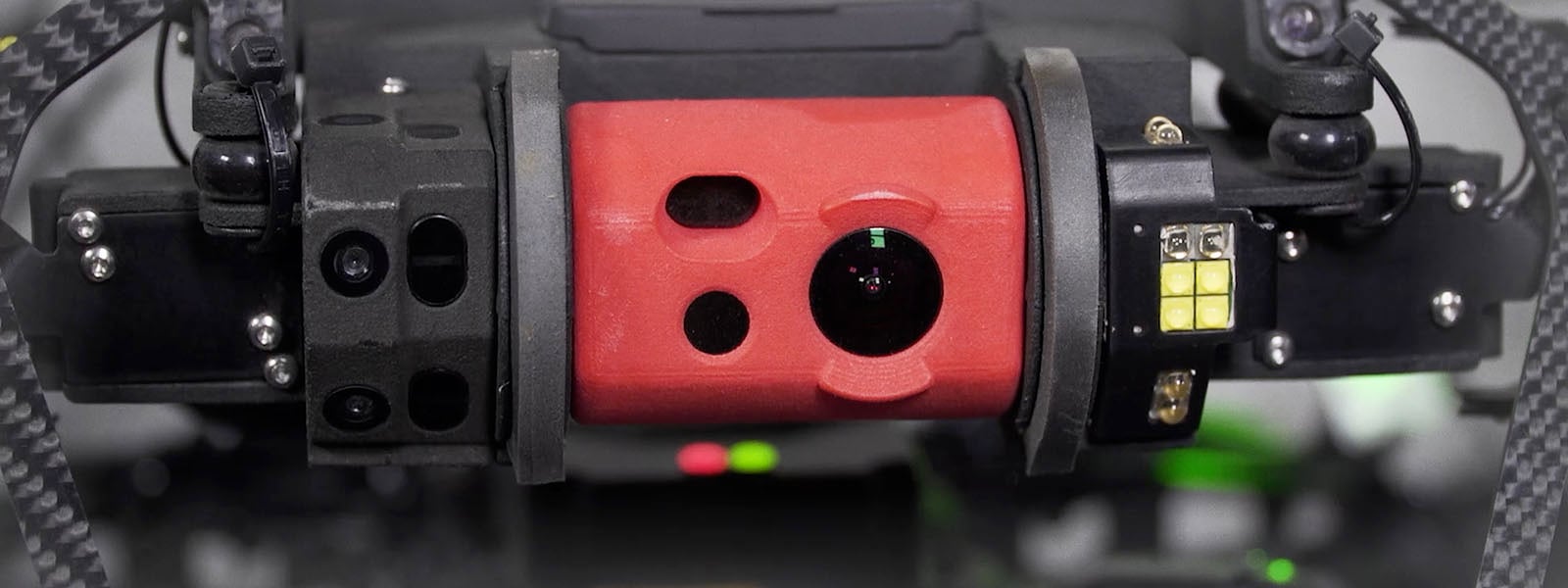

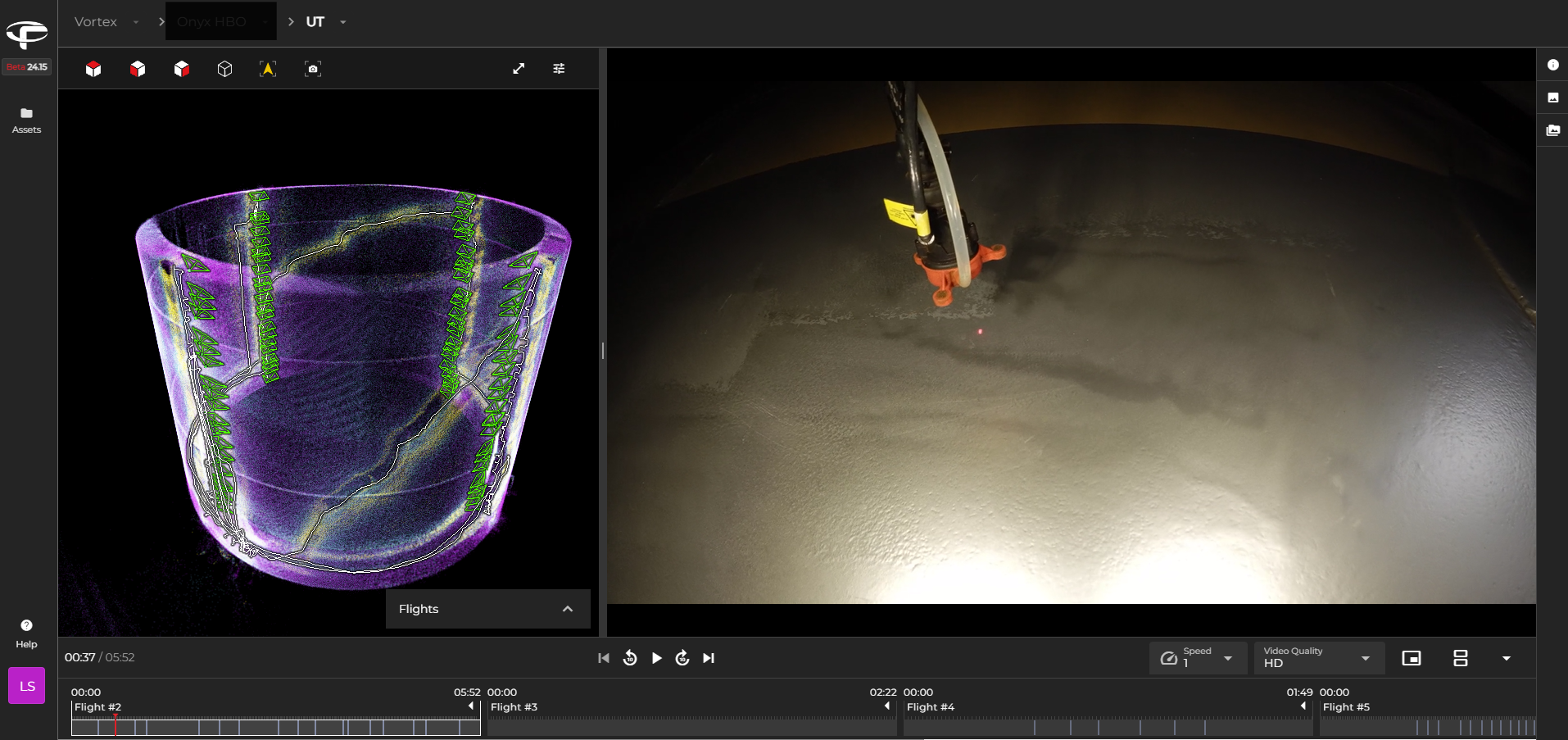

Discover the Elios 3 UT Payload

Case studies

|

Infrastructure

Infrastructure

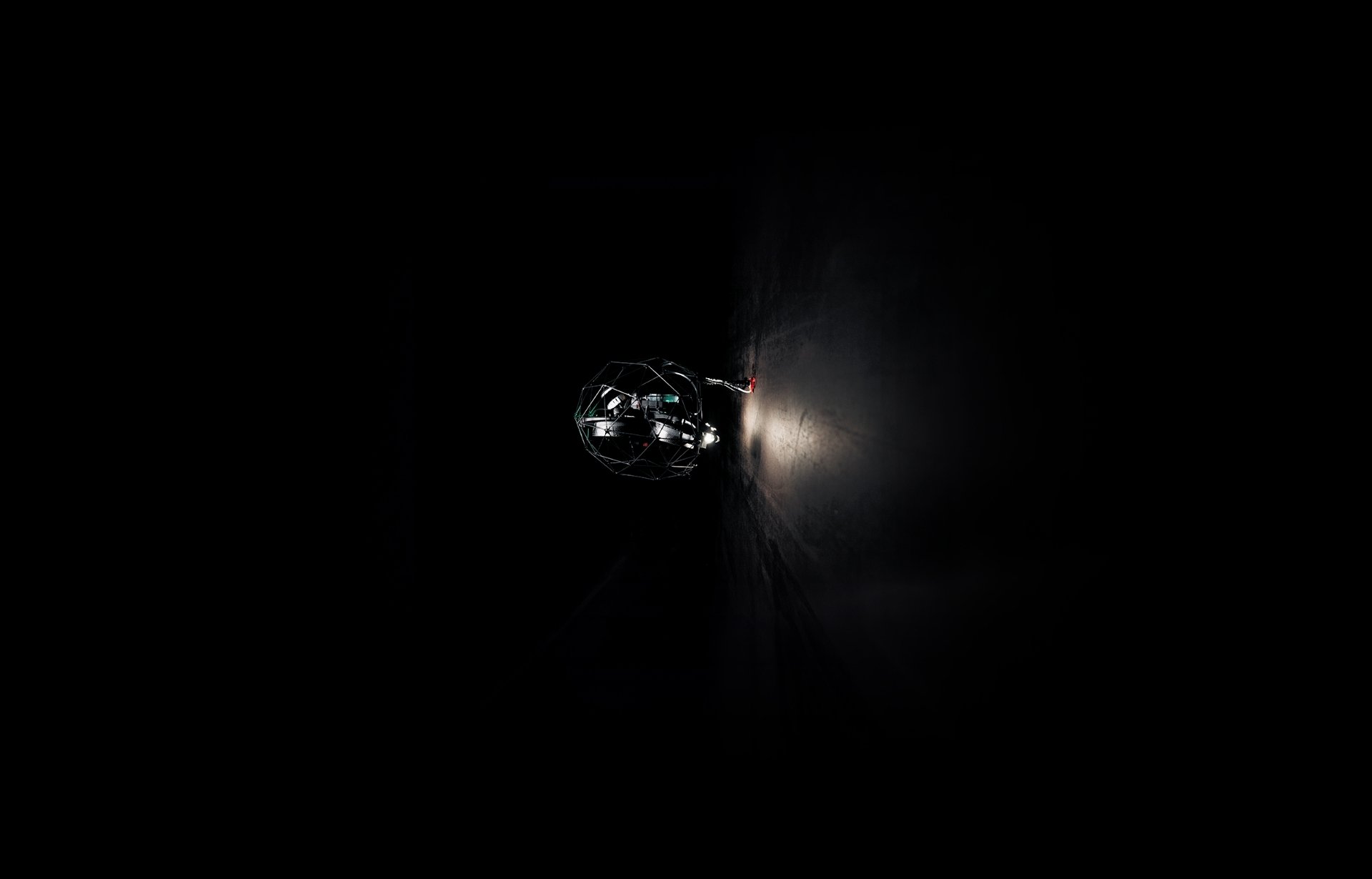

145632795500

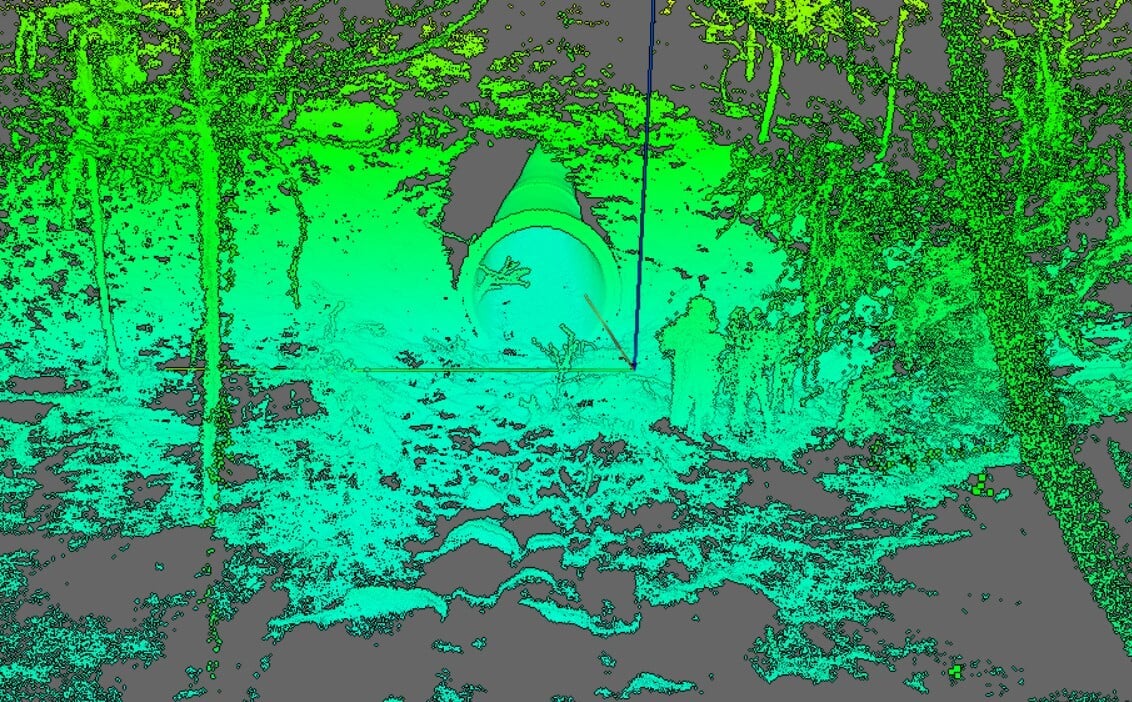

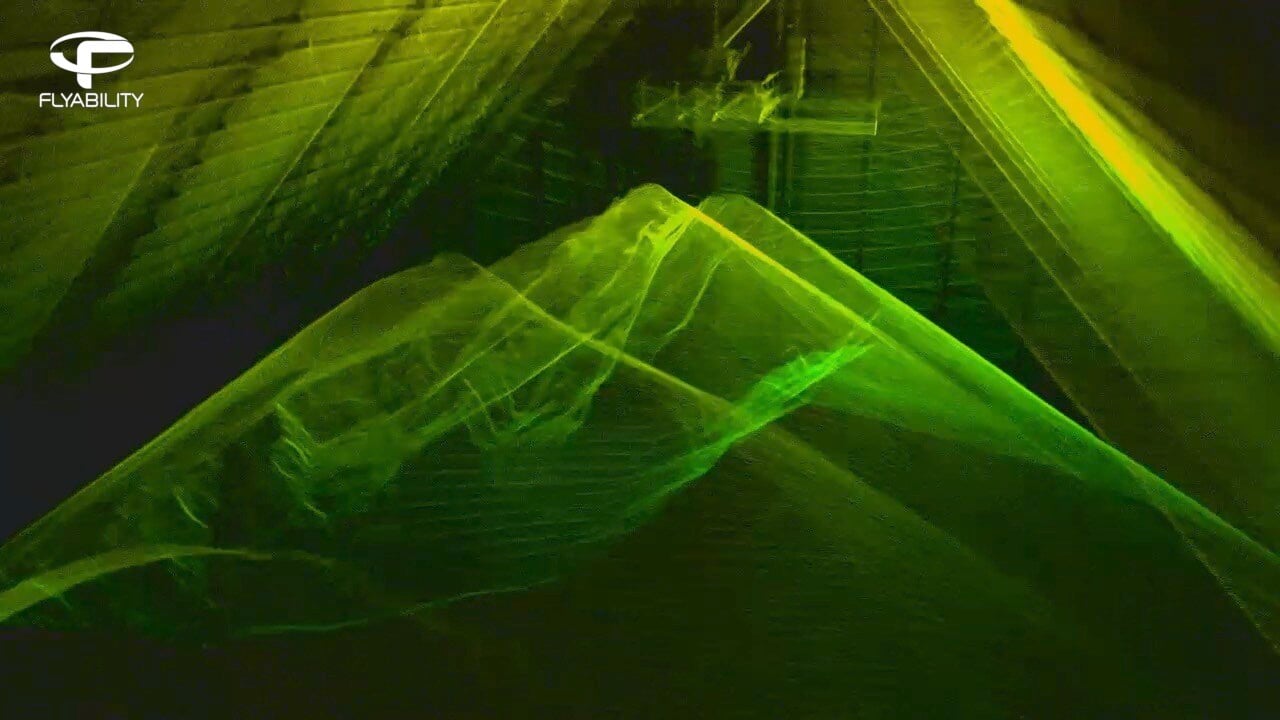

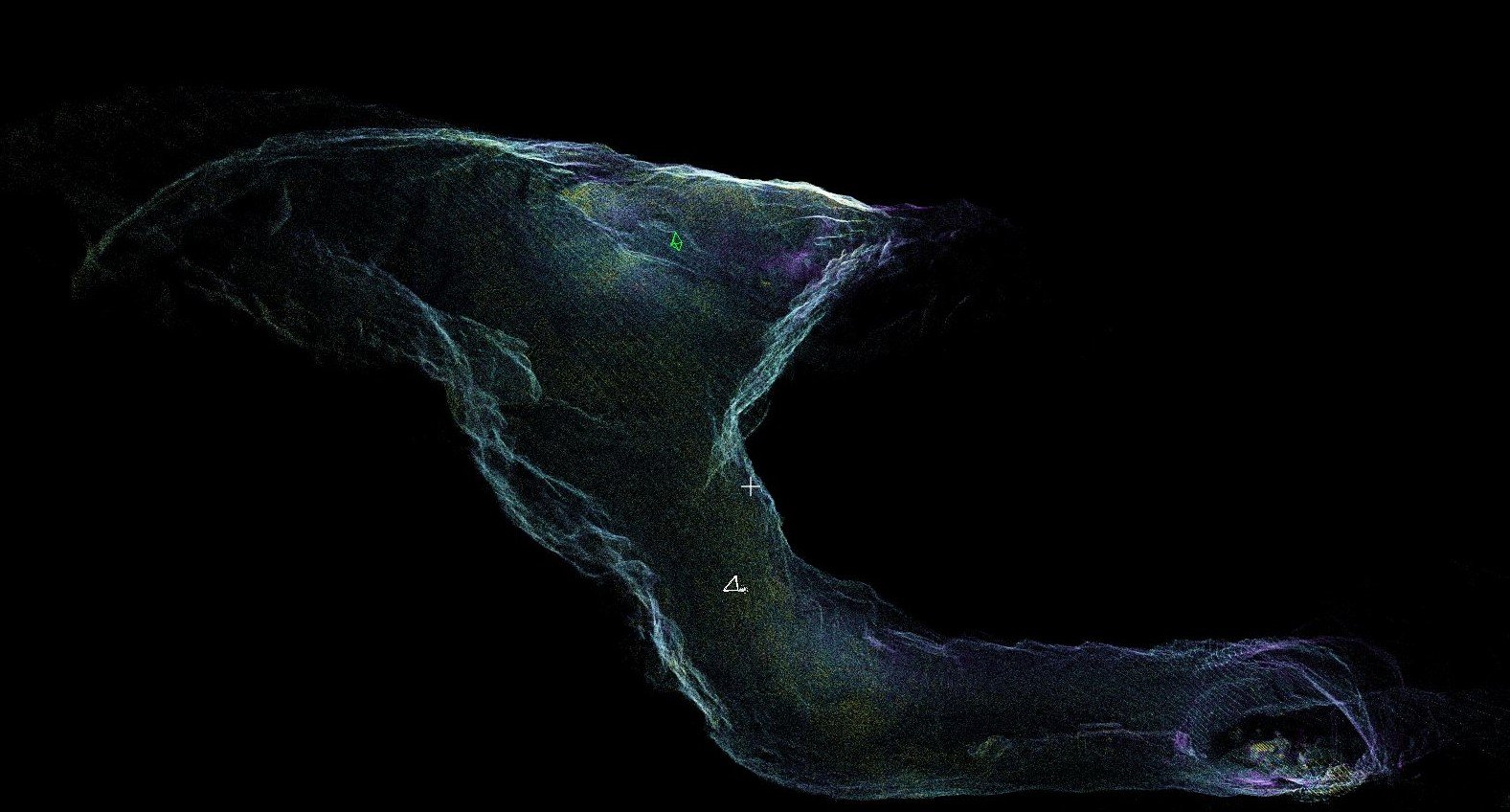

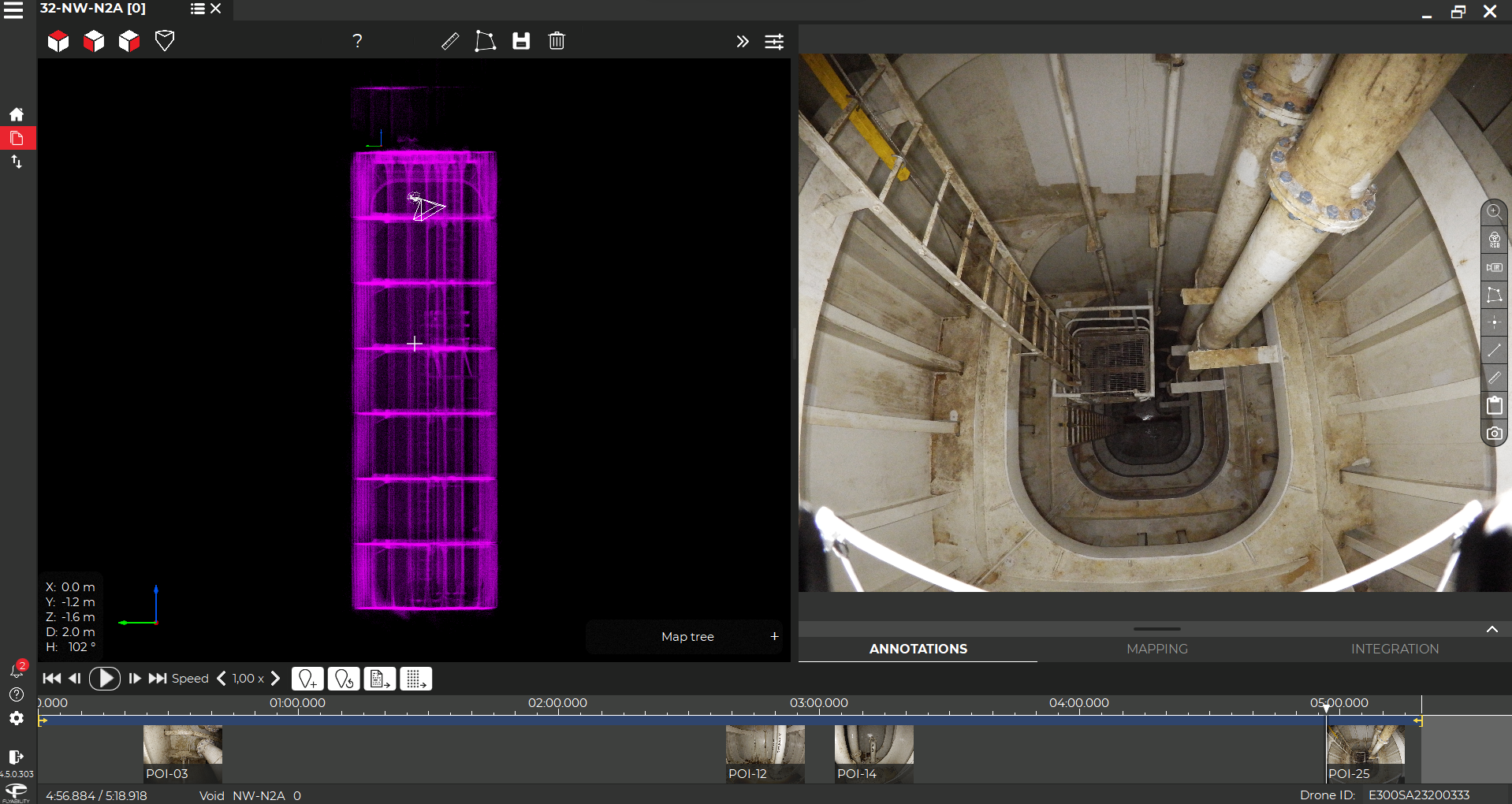

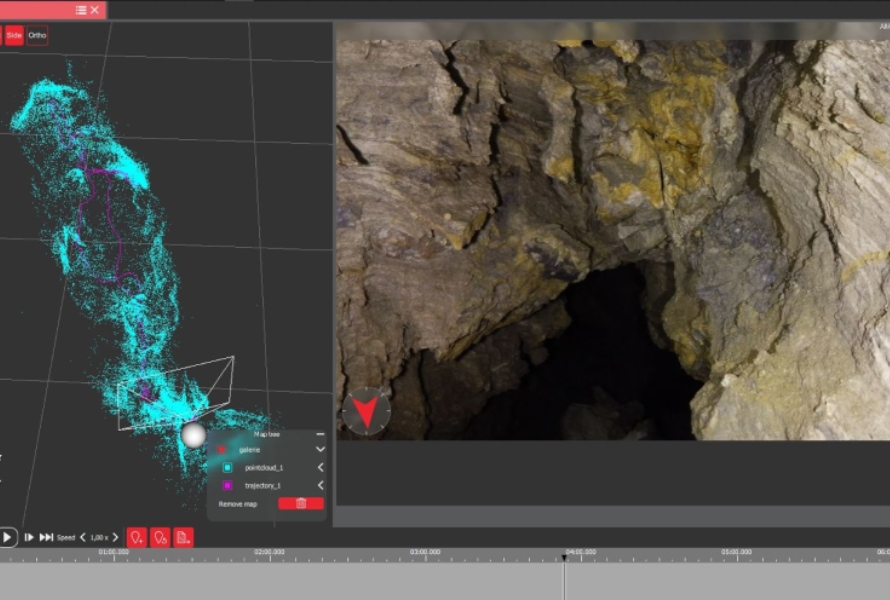

Testing the Elios 3 Surveying Payload: Mapping a 600m...

Case studies

|

General

General

166292775793

Underground drones for emergency response: investigating a...

Blog

|

Power Generation

|

General

Power Generation General

164799472751

Boiler Inspections: A Complete Guide

Blog

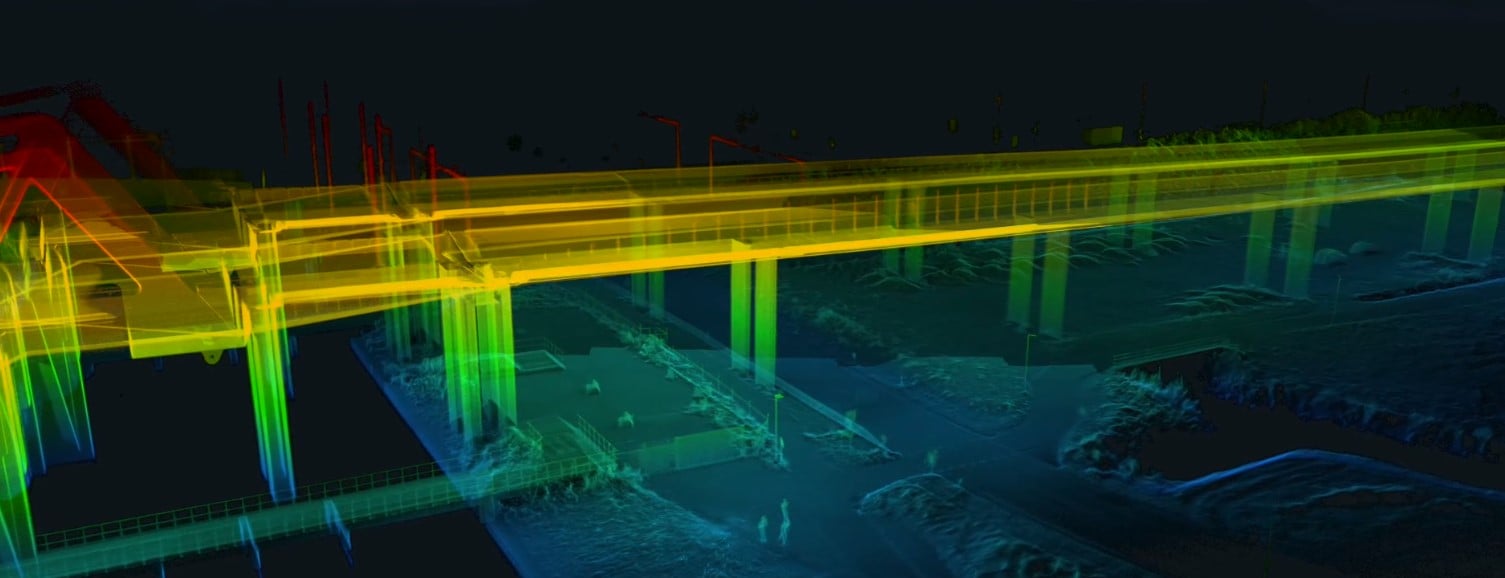

|

Infrastructure

Infrastructure

164772679838

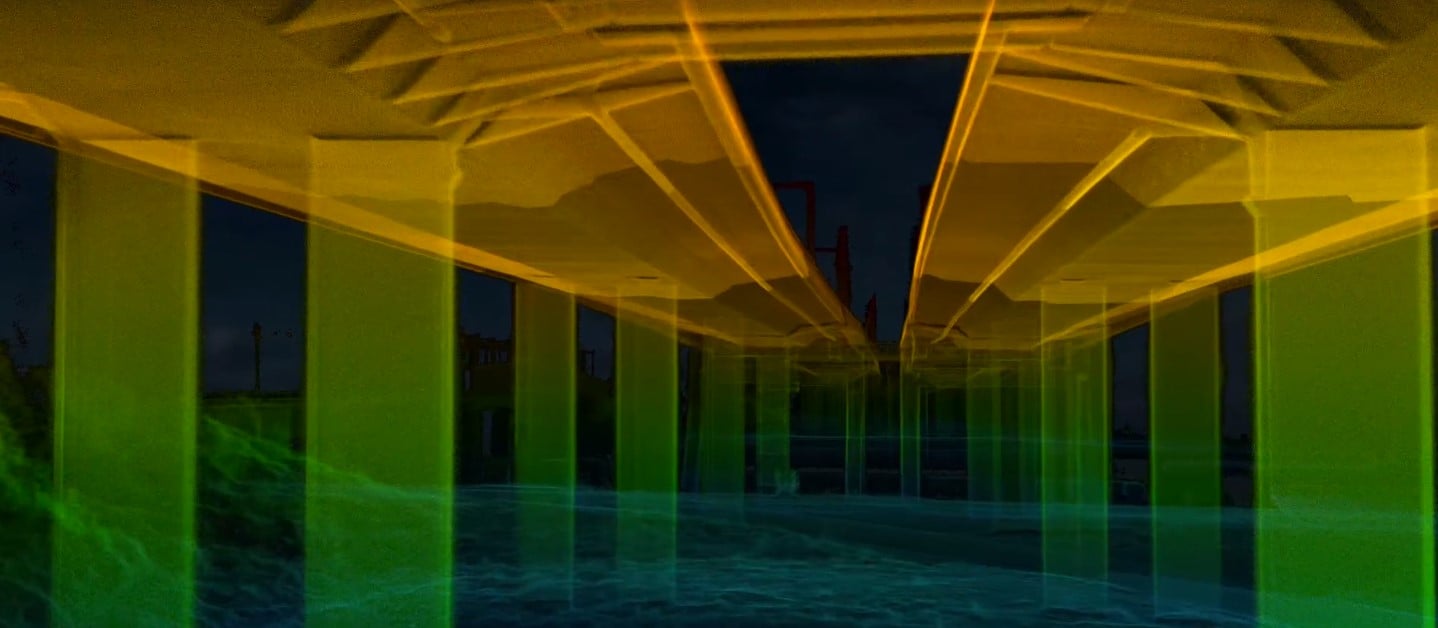

Bridge Inspections —Everything You Need to Know

Blog

|

Chemicals

|

Oil & Gas

Chemicals Oil & Gas

164752004924

A Complete Guide to Corrosion Monitoring

Blog

|

General

General

164725112604

What Does a Drone Cage Do? Use Cases, Types & Indoor...

Blog

|

Infrastructure

Infrastructure

164743513000

A Guide to How Drones are Used for Inspections

Blog

|

General

General

164721831248

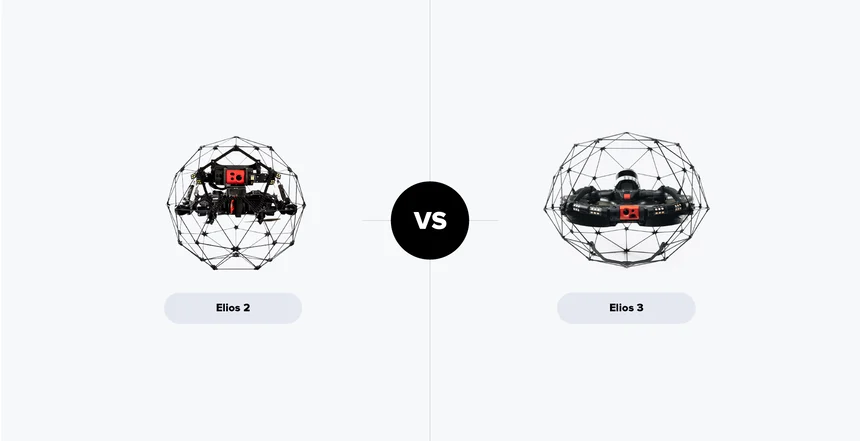

Elios 3 vs. Elios 2: How do the Flyability drones compare?

Blog

|

Sewer

|

Maritime

|

Mining

|

General

Sewer Maritime Mining General

164719776790

What Is a GPS-DENIED Drone?

Blog

|

Mining

Mining

164665724584

How Mine Drones Are Improving Safety and Optimizing Mining

Blog

|

Power Generation

Power Generation

164583719465

POWER PLANT MAINTENANCE: WHAT IS REQUIRED AND HOW DRONES...

Blog

|

Sewer

Sewer

164385558606

The Reality of Sewer Inspections—Everything You Need to Know

Blog

|

Power Generation

|

Oil & Gas

|

General

Power Generation Oil & Gas General

164254076452

What Is Turnaround Time? What Is Downtime?

Case studies

|

Power Generation

Power Generation

163246809670

A drone stack inspection with the Elios 3 UT

Case studies

|

General

General

160689626759

Automating flight merging at a sugar refinery with the...

Case studies

|

General

General

163862259590

How can the Asset Management extension reinvent your Elios...

Infographics

|

Power Generation

Power Generation

161622486043

Elios 3 Applications in Power Generation

Webinar

|

Oil & Gas

{name=Oil & Gas, label=Oil & Gas}

160655216437

Discover the Elios 3 UT Payload

Case studies

|

Maritime

Maritime

158873985867

The Elios 3 UT Payload: avoiding 15,000 hours of work at...

Blog

|

Power Generation

|

Chemicals

|

Maritime

|

Oil & Gas

Power Generation Chemicals Maritime Oil & Gas

158837901938

How UT drone inspections elevate safety and efficiency in...

Case studies

|

Infrastructure

Infrastructure

156557512279

Disaster response: the Elios 3 in the Johannesburg gas...

News

|

Nuclear

Nuclear

156556943377

The Elios 3 RAD Wins Innovation Award at 2023 World Nuclear...

Case studies

|

Sewer

Sewer

154883483751

Bringing safer confined space sewer inspections to Sydney...

Case studies

|

Mining

Mining

154326323980

Optimizing confined space inspections: A success case with...

Case studies

|

Infrastructure

Infrastructure

154010151284

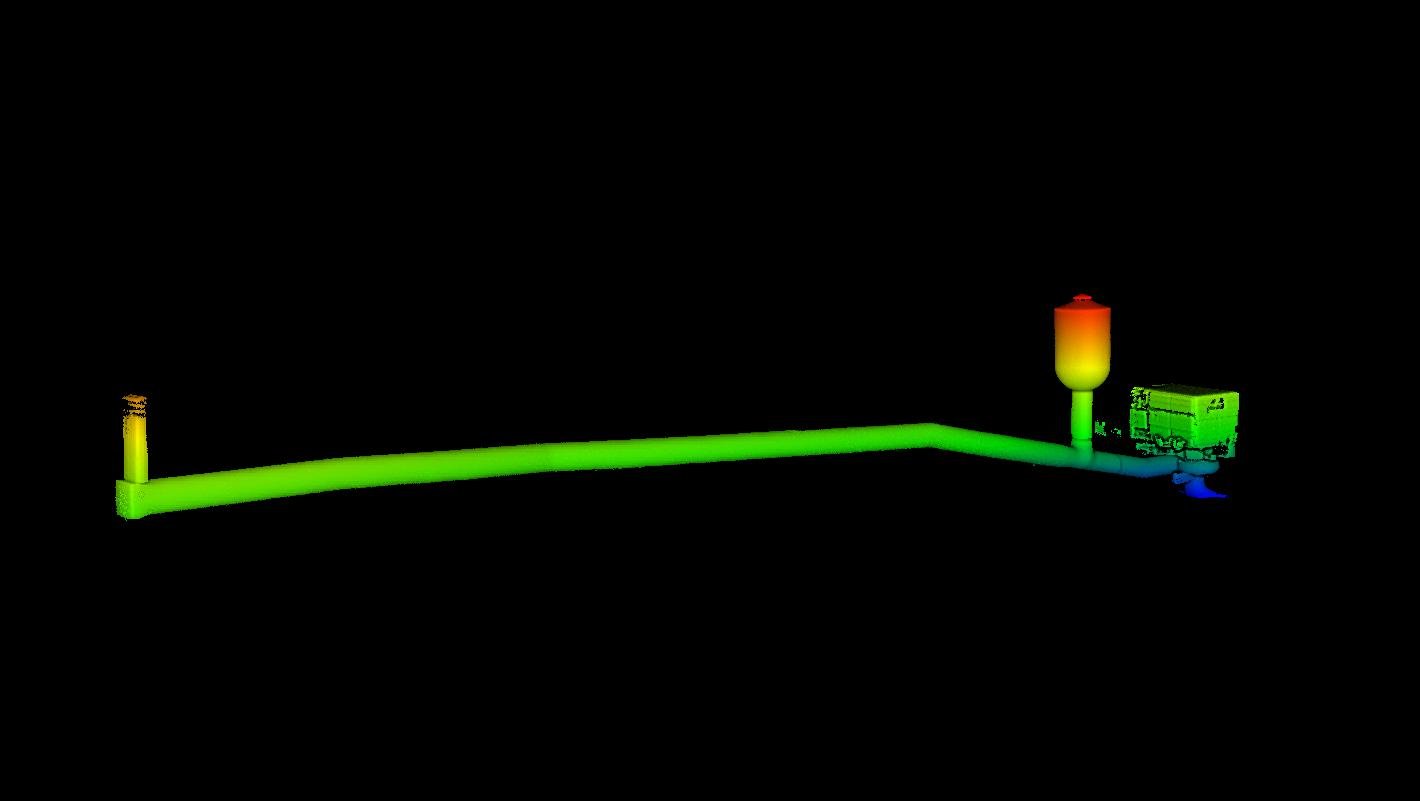

Mapping 13 kilometers of underground technical galleries in...

Case studies

|

Power Generation

Power Generation

153217186454

Saving over $1 million: wind turbine inspections with the...

Case studies

|

Public Safety

Public Safety

152854151297

Bringing the Elios 2 and Elios 3 to firefighting

Case studies

|

Power Generation

Power Generation

152606600547

Surveying a disused coal plant with the Elios 3

Case studies

|

Power Generation

Power Generation

152594999356

Power station inspections in Hong Kong with the Elios

Case studies

|

Mining

Mining

150814375275

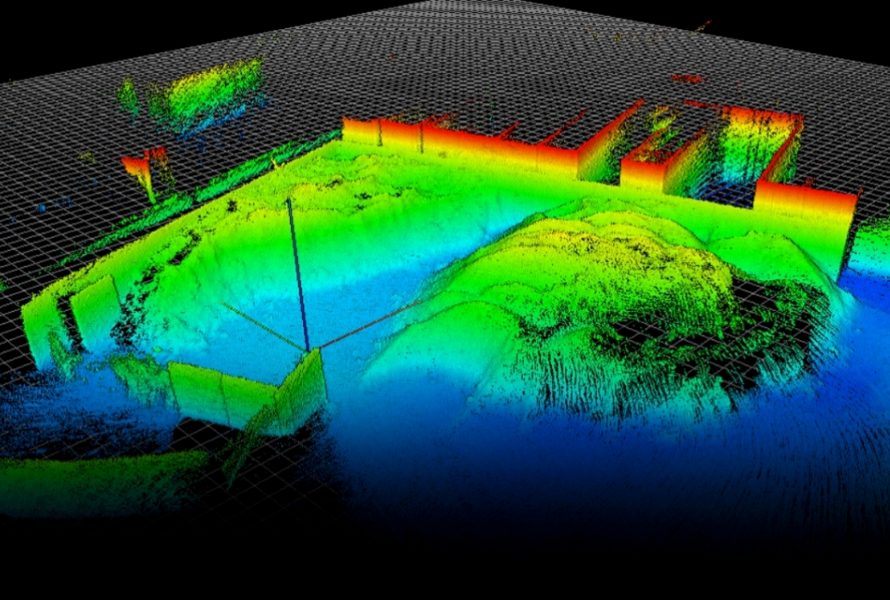

Surveying Old Workings in a Mine with the Elios 3

Blog

|

Sewer

|

Mining

|

General

Sewer Mining General

147423405988

Taking the pressure off pilots: Return-to-Signal for the...

Case studies

|

Power Generation

Power Generation

147553752151

Analyzing a 35-meter dam surge tank with the Elios 3 in...

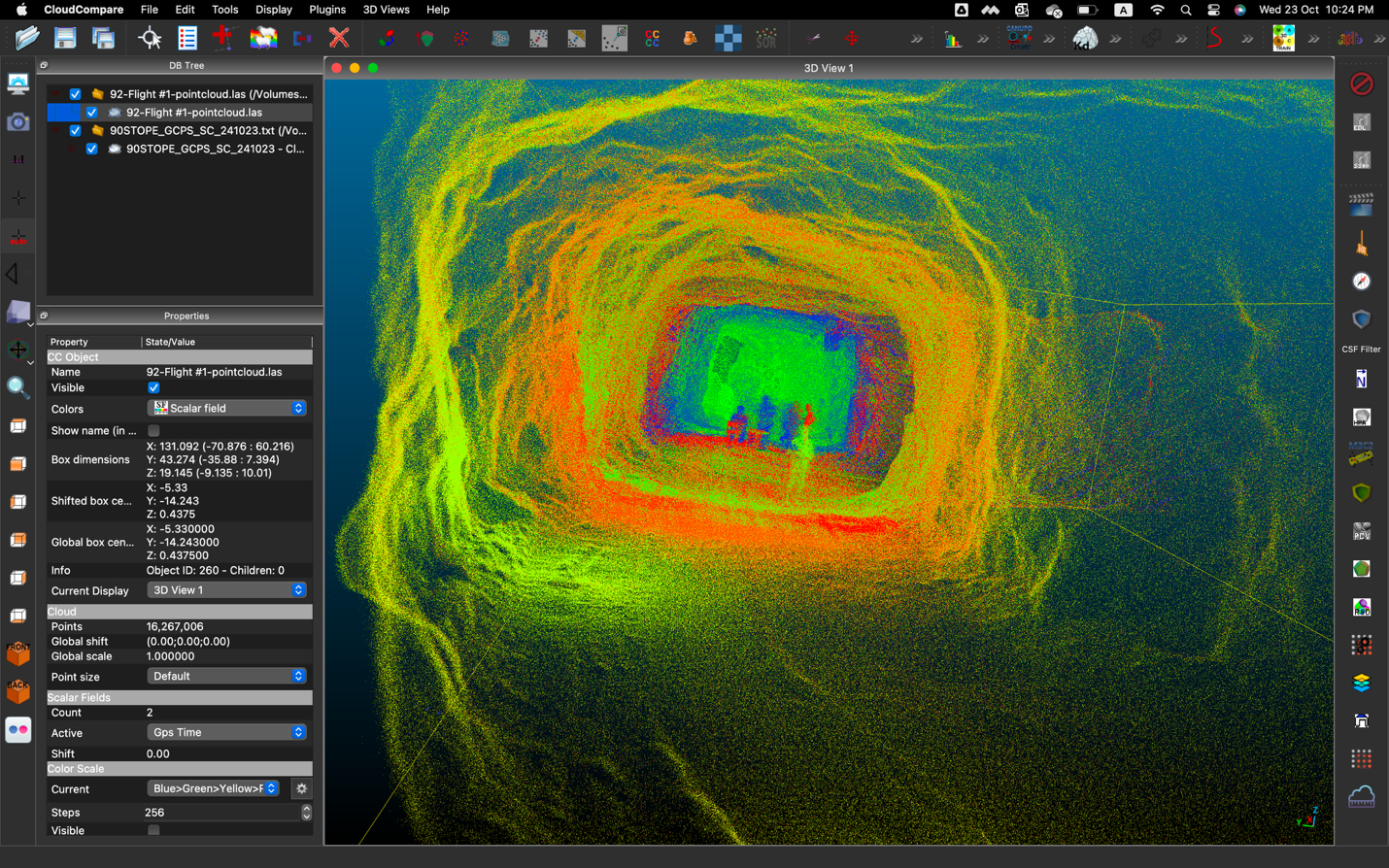

Case studies

|

Mining

Mining

146815429187

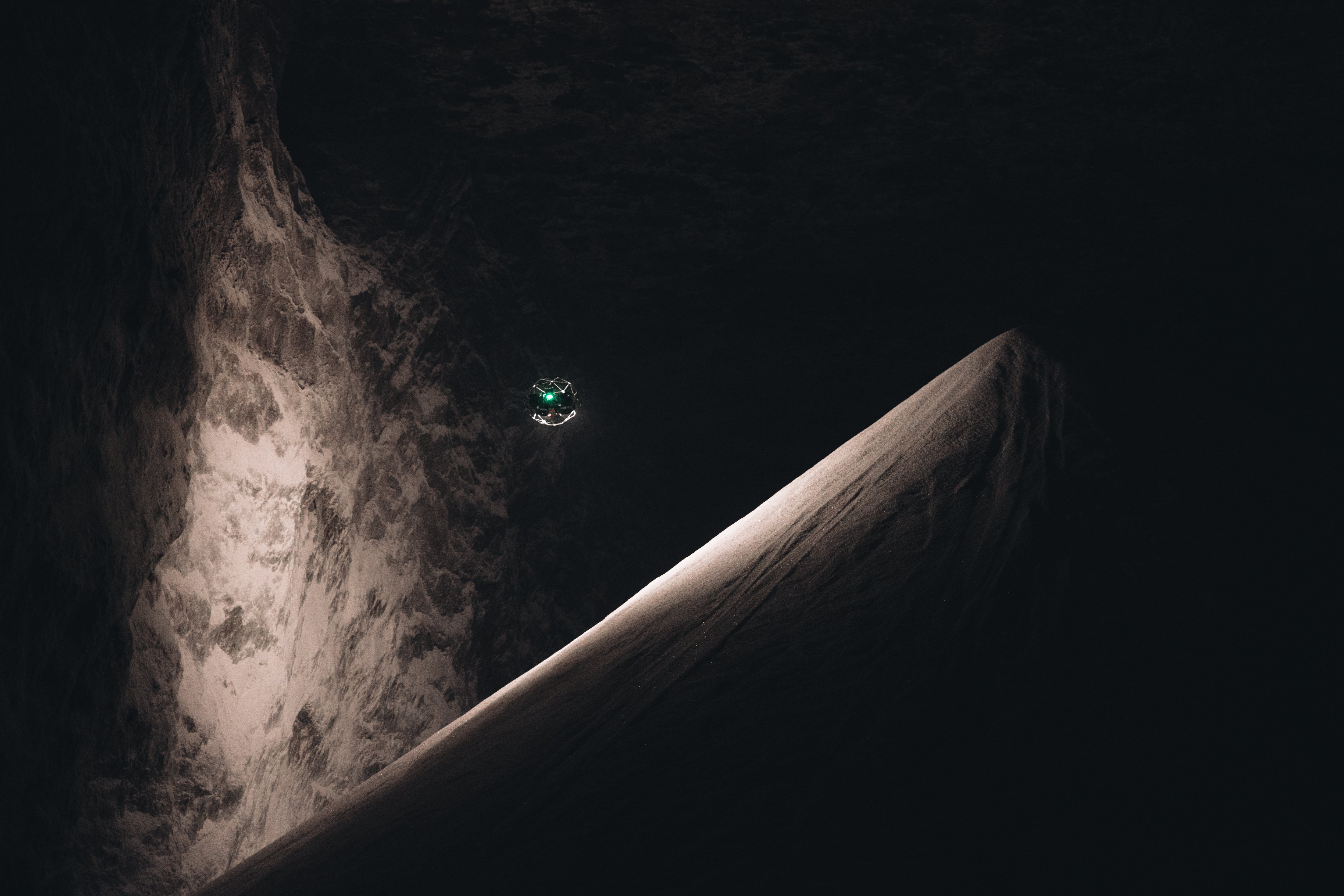

Testing The Elios 3 Surveying Payload at ICL Boulby Mine

Case studies

|

Cement

Cement

146466826811

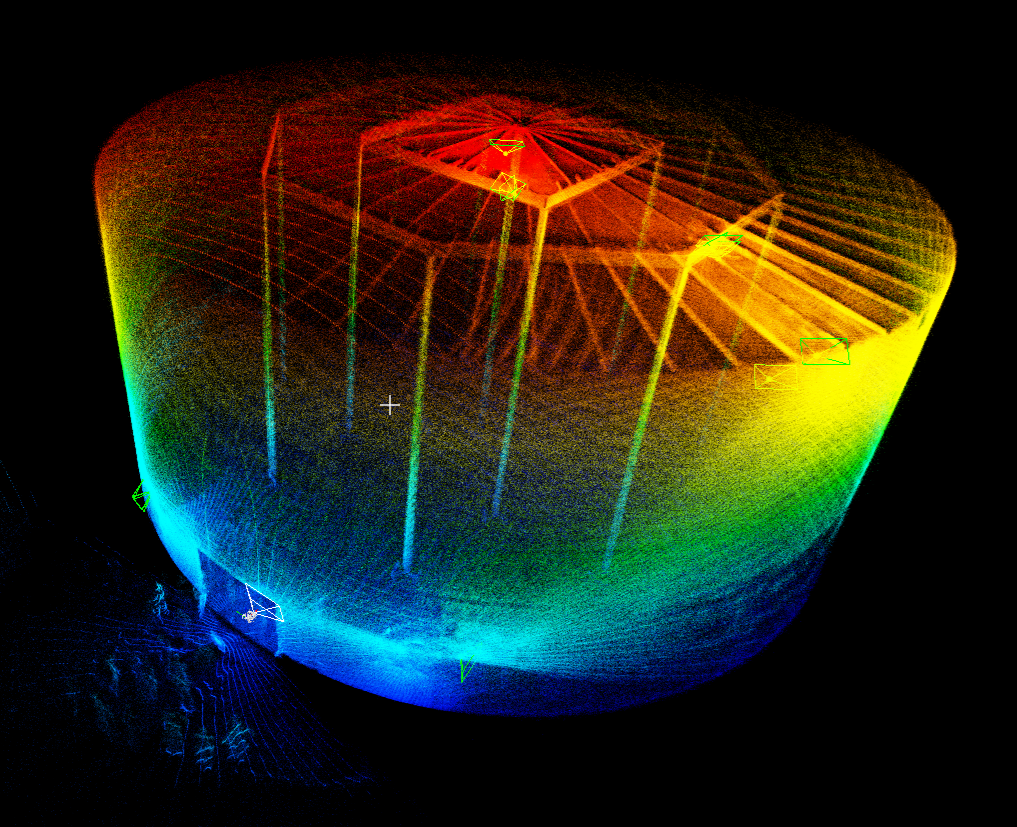

Using the Elios 3 drone to monitor stockpiles at a cement...

Case studies

|

Power Generation

|

Nuclear

Power Generation Nuclear

145290841353

Unlocking NDT inspections for power generation with the...

Case studies

|

Maritime

Maritime

144058337121

Inspecting 63 tanks with 2 drones in 2 weeks

Blog

|

Mining

|

General

Mining General

143595028225

How to create a georeferenced 3D model

Case studies

|

Maritime

Maritime

142671208983

Remote Hull inspection saves $1 million with the Elios 3

Webinar

|

Mining

{name=Mining, label=Mining}

100011716008

How Drones Are Being Used in Mining: Addressing ATEX Issues...

Webinar

|

Cement

{name=Cement, label=Cement}

142276091564

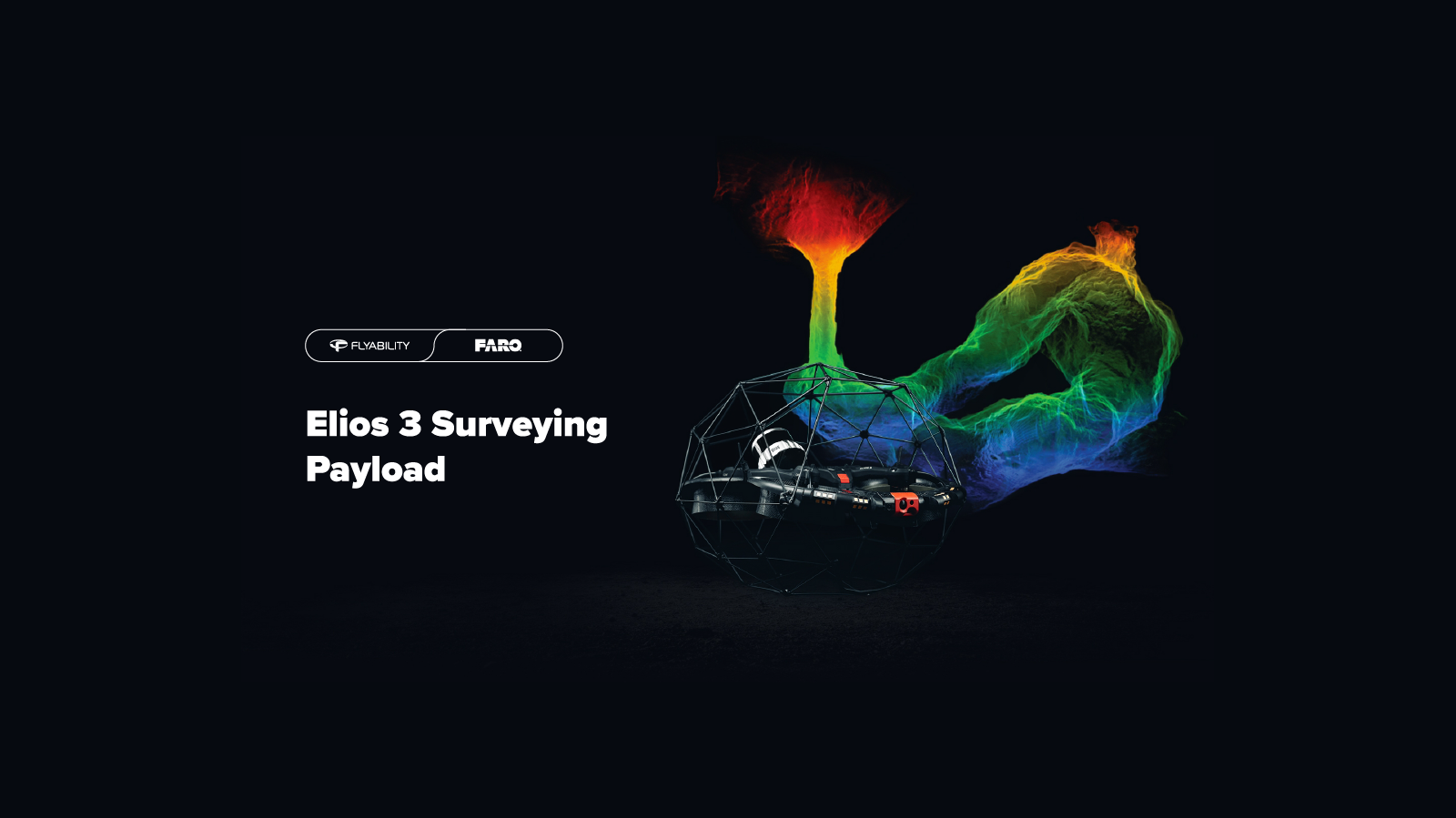

Discover the Elios 3 Surveying Payload

Webinar

|

Cement

{name=Cement, label=Cement}

143712670045

From 0 to Fleet: How Holcim adopted the Elios 3 for cement...

News

|

Cement

Cement

139845917464

Plants of Tomorrow Drone Days: Advancing Innovation in...

Blog

|

Sewer

|

Oil & Gas

|

Mining

|

Cement

Sewer Oil & Gas Mining Cement

139324176498

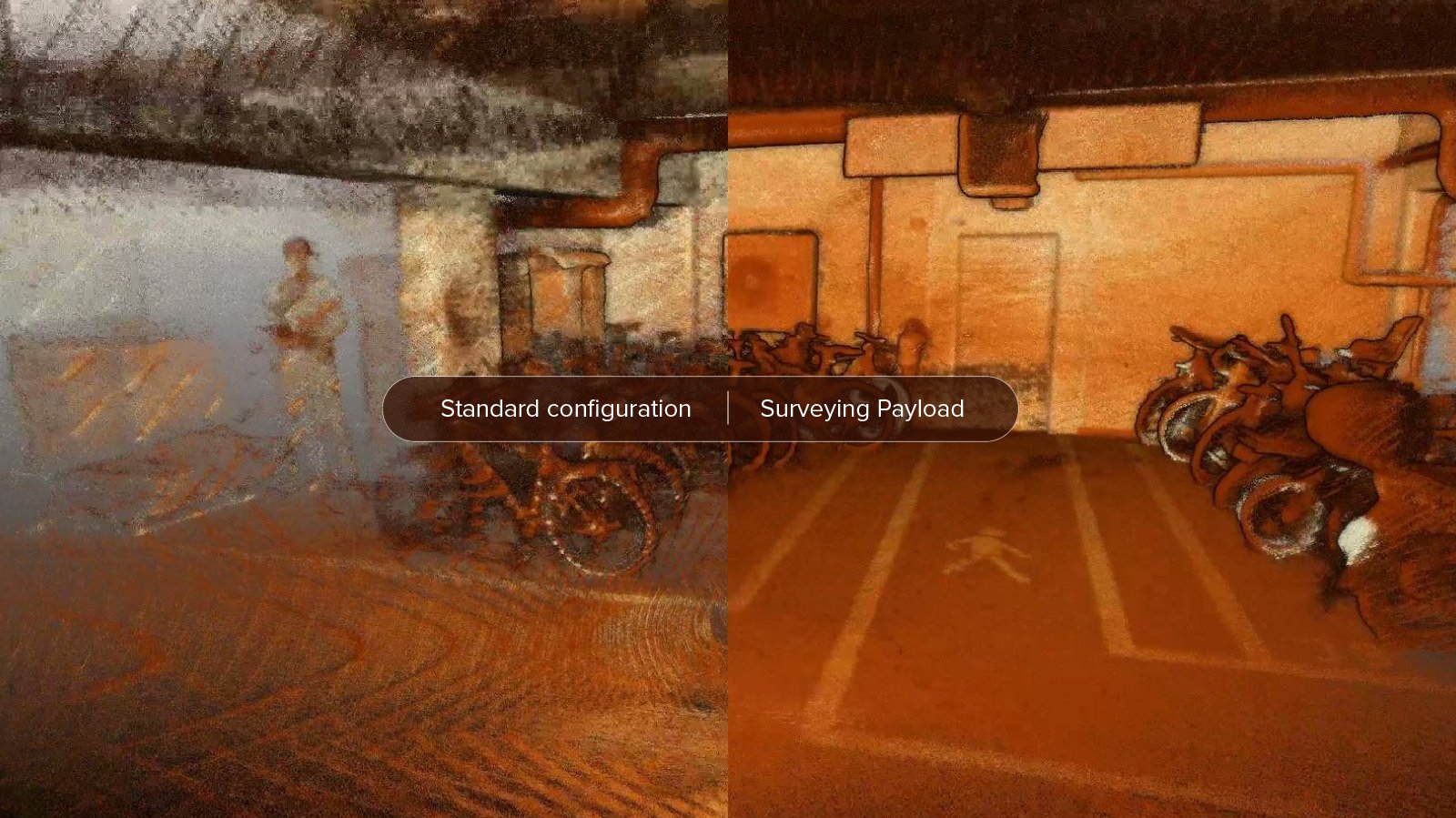

Which Elios 3 LiDAR payload is right for you? The Standard...

Webinar

|

Power Generation

{name=Power Generation, label=Power Generation}

134533606488

Radioactive: The Elios 3 for Nuclear Inspections

Case studies

|

Infrastructure

Infrastructure

136096724512

Eliminating downtime for a train station roof inspection...

Case studies

|

Nuclear

Nuclear

133210084904

Interview: Elios drones at Sellafield, Europe's largest...

Case studies

|

Cement

Cement

130581808237

Identifying chimney tower faults with the Elios 3 at a...

Case studies

|

Infrastructure

Infrastructure

130436053279

Inspecting a railway bridge inside and out with the Elios 3

Case studies

|

Mining

Mining

125072056375

Using the Elios 3 to improve site safety on a mine in...

Case studies

|

Mining

Mining

124157182340

Mining More Efficiently at Glencore Kidd Operations With...

Case studies

|

Sewer

Sewer

123756979336

Veolia Water increase safety and efficiency of their...

Webinar

|

Oil & Gas

{name=Oil & Gas, label=Oil & Gas}

118083418243

Elios Drones in the Oil & Gas industry: Digitalizing Asset...

Case studies

|

Oil & Gas

Oil & Gas

116558412724

TEXO Case Study: Inspection of Oil Tanks on an FPSO

Case studies

|

Nuclear

Nuclear

115168022934

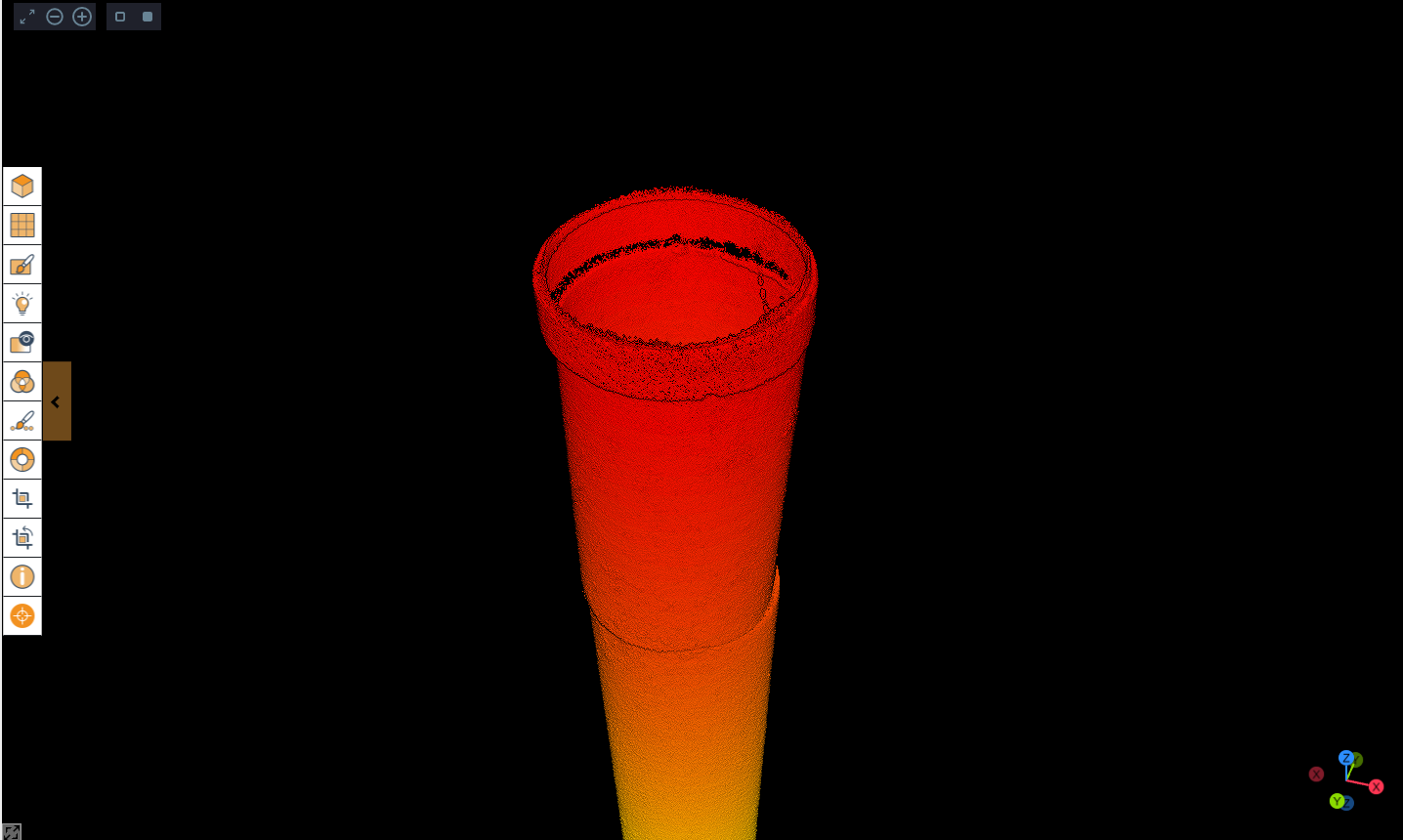

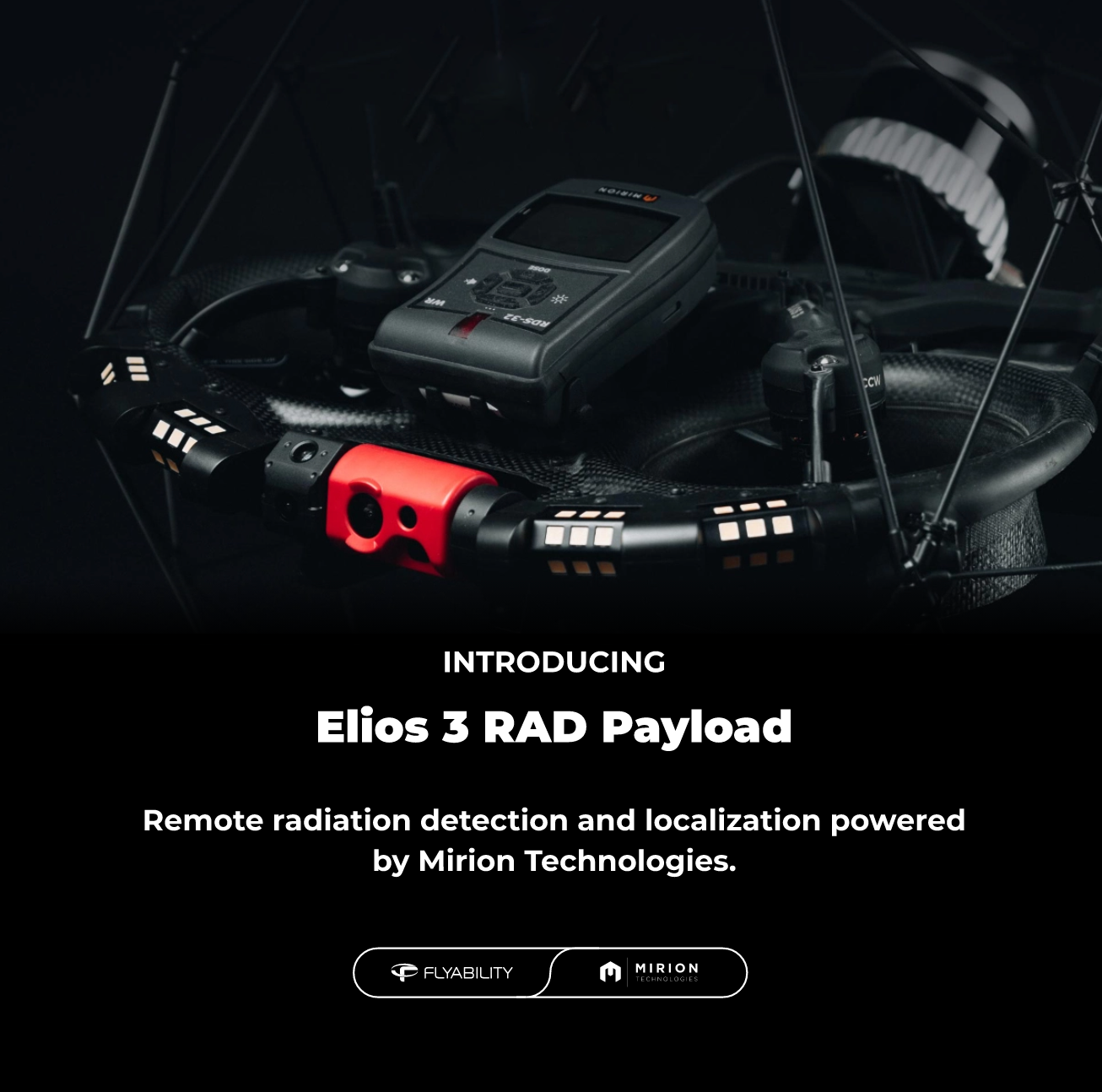

How the Elios 3 RAD payload is detecting radiation hotspots

News

|

Nuclear

Nuclear

115599057758

Flyability launches a radiation survey meter payload for...

News

|

Nuclear

Nuclear

104316492821

Flyability and Mirion Technologies announce collaboration...

News

|

Nuclear

Nuclear

99023789955

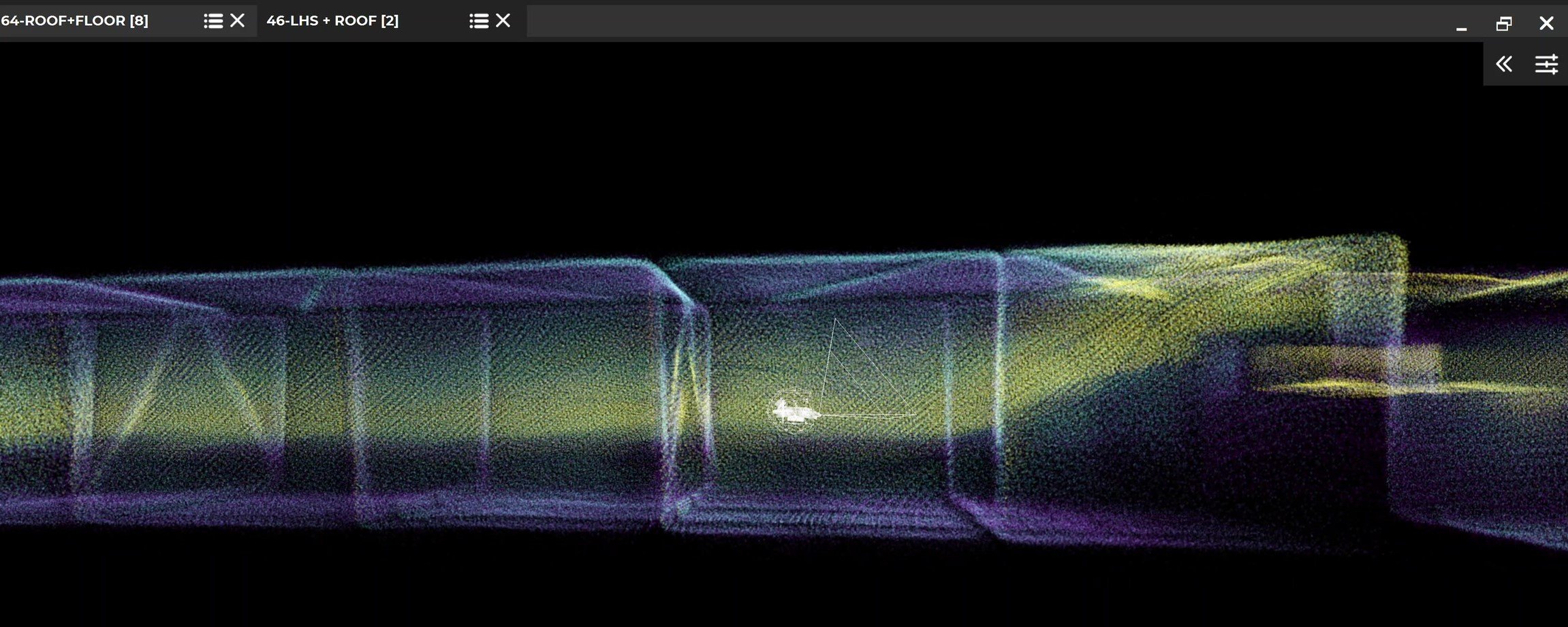

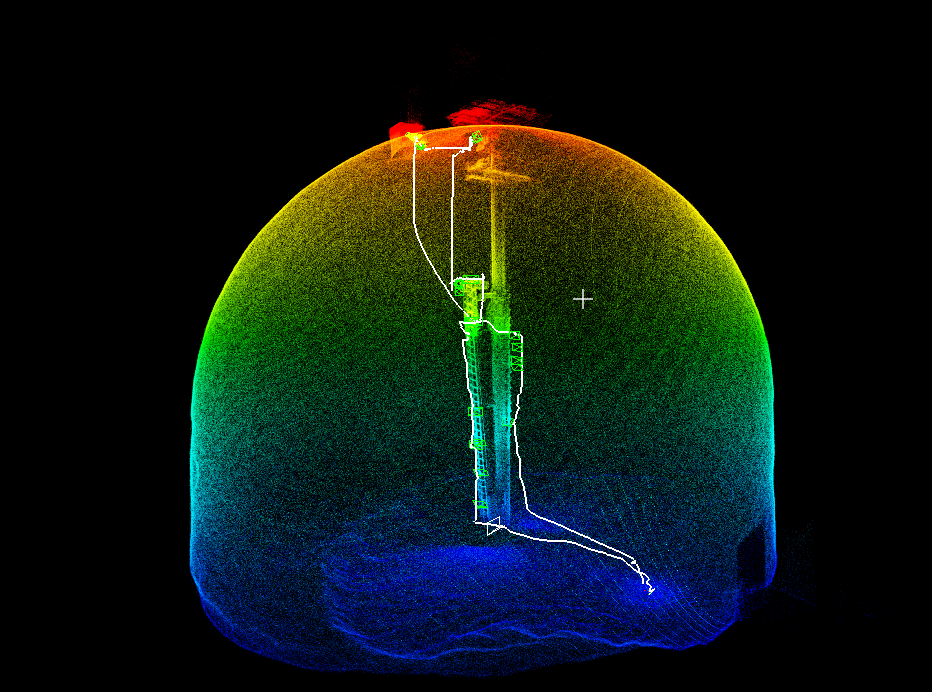

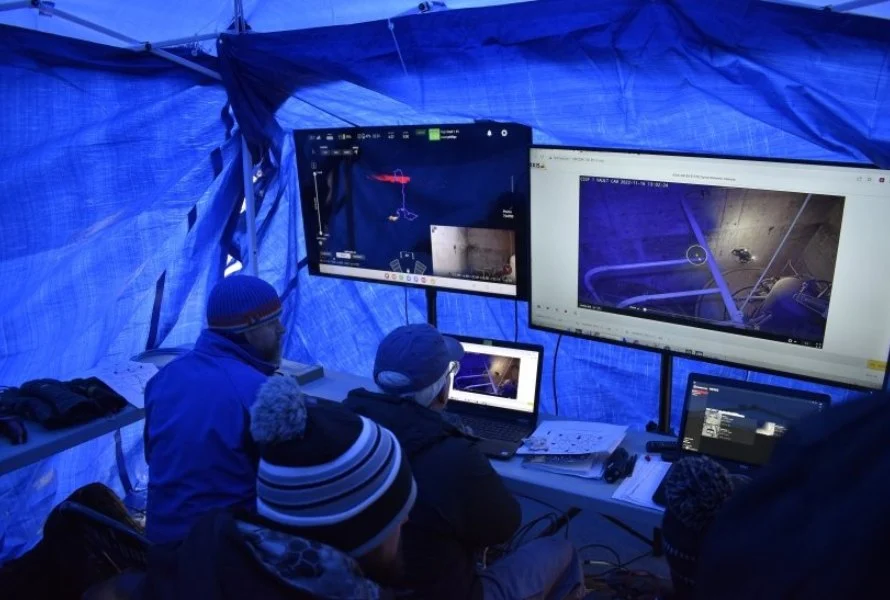

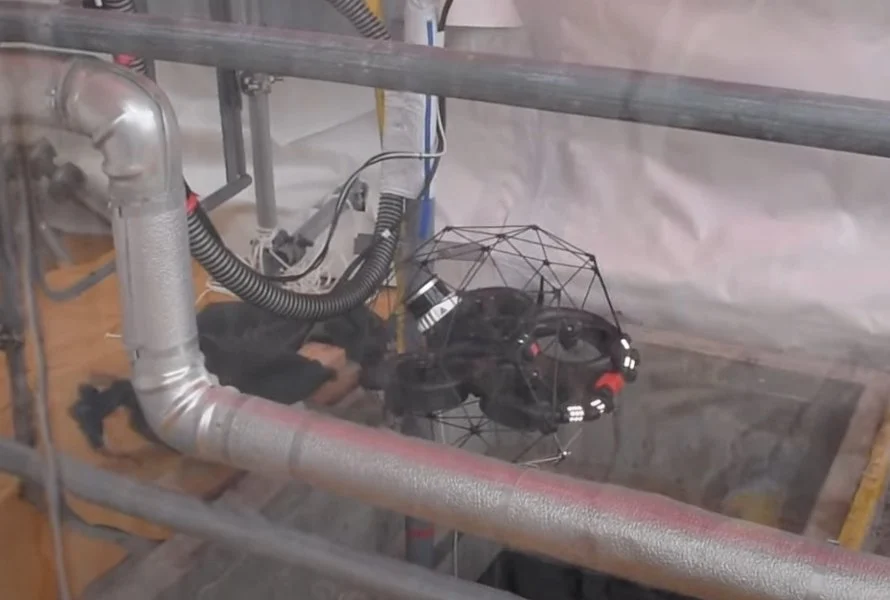

In Historic Mission, DOE Site Uses Elios 3 to 3D Map...

Case studies

|

Nuclear

Nuclear

99056168704

Elios 3 Used to 3D Map Irradiated Storage Vault at DOE Site

Webinar

79839535243

How to Make Survey-Grade 3D Models with the Elios 3 and...

Case studies

|

Cement

Cement

86441577065

Elios 3 Makes Digital Twins of New Cement Plant to Track...

Case studies

|

Mining

Mining

83333686068

3D Maps from Elios 3 Help Mining Operation Find Cause of...

Case studies

|

Mining

Mining

72501121816

Elios 3 Helps Luxembourg 3D Map Slate Mine Turned into...

Case studies

|

Nuclear

Nuclear

72503766622

Vattenfall Uses Elios 3 to Map No Go Zones in...

Case studies

|

Cement

Cement

82147951626

Major Cement Company Improves Stockpile Measurement with...

Case studies

|

Mining

Mining

72526459443

Elios 3 Stockpile Measurements Improve Safety & Accuracy at...

Webinar

79615074948

Remote Drone Inspections: How to Do an Inspection with a...

Case studies

|

Sewer

Sewer

72486101850

Elios 3’s Indoor 3D Mapping Helps City of Lausanne in Water...

Case studies

|

Maritime

Maritime

65866322606

Flyability's Elios Cuts Downtime by 80% in Drilling Rig...

News

|

Sewer

Sewer

64331569520

WinCan and Flyability partner on end-to-end solution for...

Webinar

|

Power Generation

{name=Power Generation, label=Power Generation}

57047516306

How Indoor Drones Help Reduce Radiation Exposure: New...

Case studies

|

Mining

Mining

57531353177

Testing the Elios drone at a High Altitude Mine Located in...

News

|

Mining

Mining

56282237259

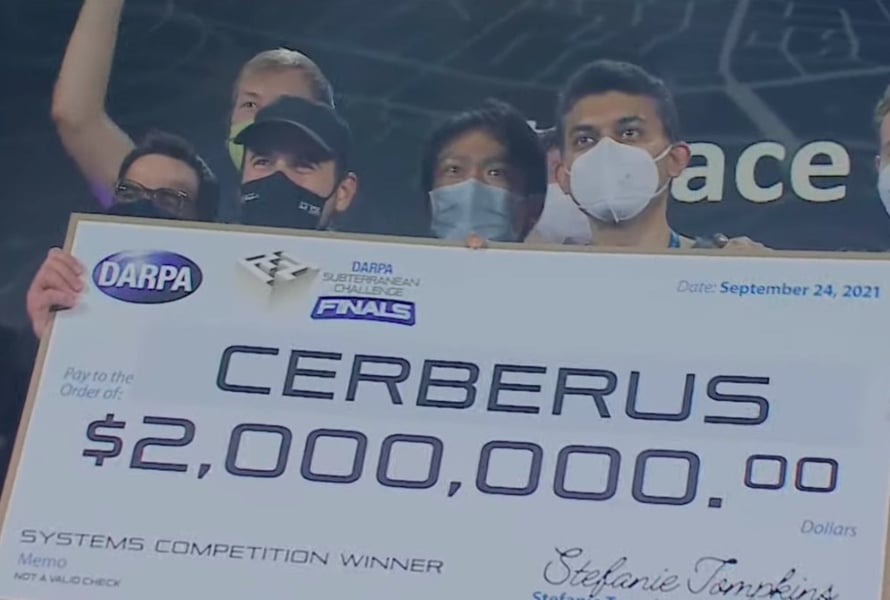

Team CERBERUS wins DARPA Subterranean Challenge, takes home...

Case studies

|

Maritime

Maritime

49959985240

DroneUp Saves 700+ Hours in ABS Tank Inspection with Elios 2

Case studies

|

Pharmaceuticals

Pharmaceuticals

46457055268

Major Pharmaceutical Company Saves Using the Elios 2 for...

Case studies

|

Sewer

Sewer

44997426538

Sewer Inspections by Drone: How Suez RV Osis Uses the Elios...

Webinar

41020798670

Drone Inspections: How to Manage Data for All Stakeholders...

Webinar

41020798669

Outdoor Drone Inspections: Case Studies and Best Practices...

Case studies

|

Public Safety

Public Safety

43598557721

Marine Firefighters of Marseille Test the Elios 2 for Ship...

Webinar

41019254489

Indoor Drone Inspections: Case Studies and Best Practices...

Webinar

41020798668

Drone Inspections: Insourcing vs. Outsourcing Your Drone...

Webinar

41020798667

The Benefits of Drone Inspections: How Inspectors Are Using...

Webinar

38266946266

[SK] Elios 2 Use Cases in South Korea (Airsens Co LTD) -...

Webinar

38461011305

Discover How Inspector 3.0 Will Change The Way You Look At...

Webinar

37617369207

How to Conduct Inspections in High Risk Environments—2 of 2

News

|

Nuclear

Nuclear

37373600133

Elios Drone Tested at the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant

Webinar

36301190647

How to Conduct Inspections in High Risk Environments—1 of 2

Case studies

|

Power Generation

Power Generation

36162191521

Drone Reduces Time Needed for Scrubber Inspection by 98%,...

Webinar

36415259434

[FR] Comment réaliser des inspections en milieux confinés...

/featured-diesel-tank-inspection.jpg)

Webinar

34303338813

HOW TO GET THE MOST OUT OF YOUR DRONE'S BATTERY LIFE—ADVICE...

Case studies

|

Food & Beverage

Food & Beverage

33505264514

Grain Bin Inspections See Improved Safety, 95% Cost...

Webinar

30895349173

DRONES IN MARINE & OFFSHORE: IMPROVING SAFETY AND REDUCING...

Webinar

|

Oil & Gas

{name=Oil & Gas, label=Oil & Gas}

30443935200

How to Mitigate Intrinsic Safety

Webinar

|

Power Generation

{name=Power Generation, label=Power Generation}

28944780058

Drones in Power Generation: How Exelon Clearsight Uses...

Webinar

|

Oil & Gas

{name=Oil & Gas, label=Oil & Gas}

28419143347

DRONES IN OIL & GAS: HOW CHEVRON USES DRONES TO IMPROVE...

Webinar

28178284817

[IT] - COME EFFETTUARE ISPEZIONI SICURE IN SPAZI CONFINATI...

Webinar

28168774149

[DE] - WIE MAN IN SCHWER ZUGÄNGLICHEN BEREICHEN SICHERER...

Webinar

28203529759

LEARN HOW API AND ASME EXPERTS ARE WORKING TO EXPAND DRONE...

Webinar

28168774118

[ES] - CÓMO REALIZAR INSPECCIONES DE ESPACIOS CONFINADOS...

Case studies

|

Power Generation

Power Generation

24381357273

$420,000 Saved in Elios Test by Argentinian Energy Company

Case studies

|

Infrastructure

Infrastructure

8352842433

Amusement Park Inspections: Faster, Safer, and More...

Case studies

|

Public Safety

Public Safety

6842075110

Safe Forensic Investigation in Liverpool Parking Lot...

Case studies

|

Public Safety

Public Safety

6823772291

Security inspection reaches new heights at China-ASEAN Expo

Case studies

|

Maritime

Maritime

6629570251

Shipping Inspections Smooth Sailing with Drone Technology

Case studies

|

Sewer

Sewer

6103334755

Inside Barcelona's Sewer System: Drone Inspection Is the...

News

|

Food & Beverage

Food & Beverage

5947952137

60,000 Bottles of Beer per Hour: This Collision-Tolerant...

Case studies

|

Food & Beverage

Food & Beverage

5945106275

Pilsner Urquell Keeps Production Running During Inspection...

Case studies

|

Infrastructure

Infrastructure

5531676195

Indoor Drones in Bridge Inspection: Between Beams and...

Case studies

|

Mining

Mining

5531400207

Indoor Drone in Underground Mining: Accessing the...

Case studies

|

Infrastructure

Infrastructure

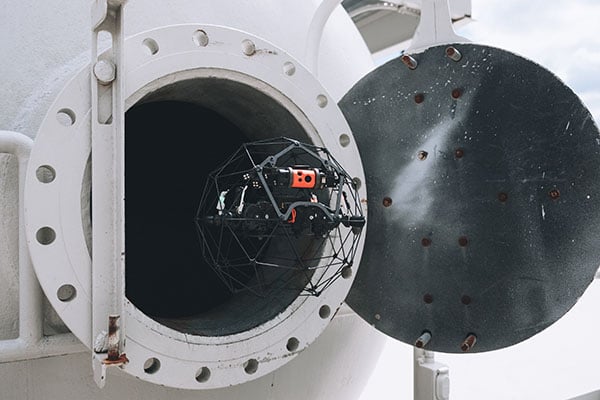

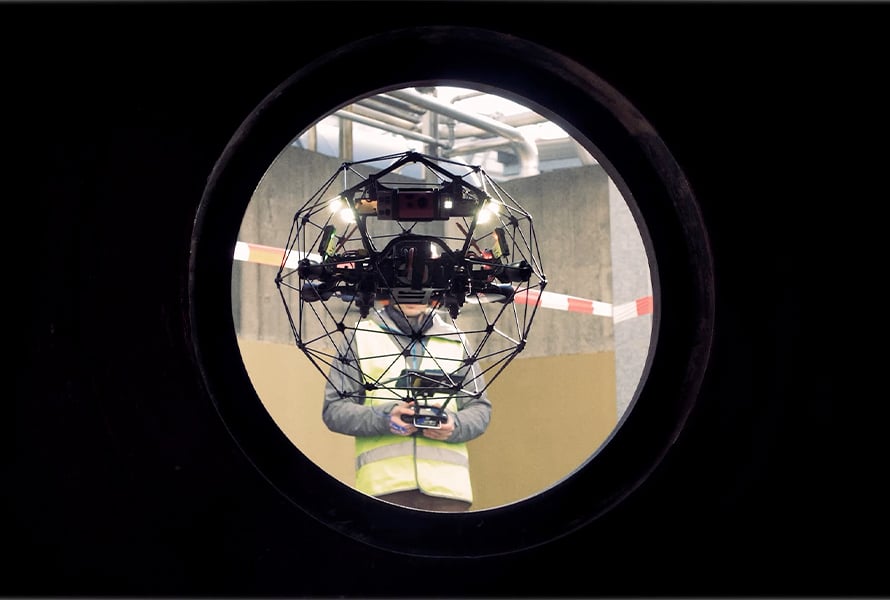

5531390572

Inspection of a jet engine test facility

Case studies

|

Maritime

Maritime

5531385620

Inspecting the ballast tank of a container ship

.jpg)